The A-Z of Addiction

This week, addiction! Why do we get hooked on things? Are video games addictive? And evidence that the gambling industry use artificial intelligence to make you more likely to keep playing. Plus, in the news, scientists discover how to turn insulin injections into a pill, a revolution in making biofuels much faster, and we find out about the science of why things roar!

In this episode

01:00 - Insulin pill for diabetes

Insulin pill for diabetes

with Samir Mitragotri, Harvard University

Millions of people worldwide are afflicted by diabetes and regularly have to inject the insulin they lack to control their blood sugar. Now scientists have developed a way to package the drug into a pill and protect it from digestion. Chris Smith spoke to Samir Mitragotri from Harvard University...

Samir - In diabetes insulin is not produced by the pancreas, or not used very well by the cells, so the sugar level in the body goes up and that has significant long term complications, such as loss of eyesight, loss of sensation. The main therapy is to take insulin. Now insulin is a protein, which means it gets digested by the stomach and, even if some insulin remains in the stomach intact, it goes into the intestine, and it cannot be absorbed from the intestine into the blood circulation. So, a long story short, you cannot take insulin as a pill, it’ll just get digested so that’s why people have to inject it into the body.

Chris - What have you done to try and surmount the problem?

Samir - We figured that if wanted to deliver insulin orally, which would tremendously help diabetics, we had to figure out three things:

We had to protect insulin in the stomach from the enzymes and the acidity in the stomach.

When insulin reaches the intestine we had to make sure that it can cross the mucus layer which is present on the inner lining of the intestine.

We had to make sure that insulin can cross the cell layer which is also present on the intestine and is connected by tight junctions.

These are the barriers which are designed by the body to keep large molecules out and we had to overcome them to be able to deliver insulin into the blood circulation.

Chris - How do you think you can do it?

Samir - That’s where ionic liquids came into the picture. Ionic liquids are a very interesting class of materials. These are basically liquid salts, so just think about your table salt which is sodium chloride. In the case of sodium chloride, the sodium and the chloride ions are very small so they form a solid. Now, imagine a large positive charge and a large negative charge molecule, when they form a salt they are a liquid, and that’s basically ionic liquid. These ionic liquids have very interesting properties; they can stabilise proteins like insulin, they can overcome the barrier of the mucus, and they can also open the tight junctions by acting on the cells of the intestine. We tried a number of ionic liquids and it turned out one in particular is very effective in overcoming all three barriers in a single formulation and that’s what allowed oral delivery of insulin in our study.

Chris - My question is then, what is the liquid in question and how do you mix it up with the insulin so that you end up with a form of insulin that will get in via mouth into the bloodstream?

Samir - The ionic liquid that we used has two components. The first component is choline, which is basically a dietary supplement that many people take. And the second molecule in the ionic liquid is geranic acid, which is also a naturally occurring molecule present in lemongrass and cardamom. When we combine them they form this ionic liquid that we call CAGE which stands for choline and geranic acid eutectic, and we add insulin to it and essentially make a suspension and fill that liquid in a capsule, and that’s the formulation that we deliver.

Chris - Does it work? I mean, when you take this, does the insulin get protected from the stomach acid and does it end up getting into the bloodstream?

Samir - It works very well. We did a number of studies. We looked at the ability of CAGE to protect insulin against the enzymes and it was quite effective. We also looked at the ability of CAGE to reduce the mucus barrier by lowering its viscosity and it worked very well. And the third set of studies we also looked at how well this CAGE worked in opening the tight junctions of the intestine, and that also worked very well. When we delivered this insulin pill to rats, we saw a significant reduction of the glucose levels, which is an indication of insulin getting into blood circulation.

Chris - Was it as good or better than if you inject insulin? Does it work equivalently well?

Samir - You had to deliver a little bit more insulin by oral route compared to an injection, but the end result is much better than what we got with injection. And what I mean by that is when you inject insulin by needles it is all delivered very quickly into the blood, so the glucose level goes down quickly and the insulin is eventually cleared and the glucose level comes up quickly. So there is a big jump in insulin concentration and a big reduction as opposed to that when you deliver it orally you see a long lasting effect of insulin on the blood glucose level. So a a single oral pill can reduce the glucose levels for a much longer time than an injection can.

Chris - And is this safe? Because if you’re capable of bypassing the normal defences of the intestine which are there to keep things that shouldn’t be going in out, is there a possibility that other things will end up sneaking in alongside the insulin that you do want and that could be bad for the patient?

Samir - In the study we did a very interesting experiment. We gave the ionic liquid CAGE to the rat by itself first, we waited for half an hour and then gave insulin by itself. And, interestingly, what we found is that the treatment where one is followed by the other does not work as well as both delivering simultaneously. What that tells us is that insulin has to be dispersed in CAGE, in the ionic liquid, for it to work. And what it means for safety is that now if you think about other molecules, which are present in the intestine but are not part of the CAGE insulin formulation, they have a much less chance of getting into the circulation compared to insulin.

07:29 - Cancer risk in the air

Cancer risk in the air

with Irina Mordukhovich - Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

They look after us on countless flights, fulfilling our demands for tea and sandwiches. But it turns out that being a flight attendant is not without its risks. A new study has found that flight attendants have a much higher cancer risk than the general public, in part due to dangerous radiation that comes in from space. To learn more, Adam Murphy spoke with Irina Mordukhovich...

Irina - We found higher rates of breast cancer, melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers among flight attendants, and we also found higher rates of other cancers. The estimates were less precise and the number of cancers in our study was also lower for those cancers. So I would say our main findings are for breast cancer, melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer, but we were also interested to see that other cancers that we looked at were present at higher rates as well. Those were uterine, cervical, grouped gastrointestinal cancers, and thyroid cancer.

Adam - How did you go about finding that?

Irina - The cancers were self-reported by the study participants. We have a study that’s been going since 2007 called “The Flight Attendant Health Study,” and the goal of the study is to track flight attendant health in relation to their work and to track their health over time. This study that we’re reporting here is from the 2014/2015 wave of the study and we recruited 5,300 flight attendants and we asked them about their work history, their health history, their work exposures, and different personal characteristics.

Adam - So how much more likely were flight attendants to suffer from these cancers than the general population?

Irina - It depends on the cancer. For breast cancer it was about 50 percent higher taking into account age, and for the skin cancers it was between three and four times higher actually, so the skin cancers were much higher.

Adam - What might have caused these cancers to develop in flight attendants instead of in other people?

Irina - We don’t know for sure. We have some ideas. In terms of the work factors that could be related to cancer in flight attendants there are a number that we know about. One of them is cosmic ionising radiation; that’s probably the main one that we’re concerned about. It’s ionising radiation that comes from outer space and by the time it reaches ground level it’s at very low levels, but at altitude it’s much higher and so flight attendants and pilots are actually considered to be radiation workers. In the US there the most highly exposed radiation workers relative to any other occupation. Currently, there aren’t any protections in place. In the European Union and in a few other countries flight attendant schedules are changed to minimise their exposure to ionising radiation, and that’s not the case in the US right now.

Other exposures that flight attendants have are to UV radiation because UV radiation is much higher at altitude as well and comes in through the windows in the aeroplane. Then also, the other factor that we worry about is circadian rhythm disruption which comes from working shifts, and working nights, and crossing time zones. So your sleep cycles get disrupted and that circadian rhythm disruption is linked to cancers in a number of studies, and a number of epidemiologic studies, and it’s also considered to be a probable carcinogen.

Adam - Wow! Is there anything that should be done to protect flight attendants, American flight attendants especially or is it just schedule changes, or is there anything we can do to the planes?

Irina - I don’t think there’s anything that can be done for the planes because usually the way you protect from radiation is lead or other heavy metals as well. I’m not an engineer but I don’t think you can build a layer of lead into the aeroplane and still have it be able to fly. In terms of protecting flight attendants, as far as I know there’s just the schedule changes and also, of course just living as healthy a lifestyle as possible outside of the job.

Adam - What about frequent flyers; people who are in planes a lot? Is there any danger to those people or is it just a flight attendant problem?

Irina - Frequent flyers have not been studied in terms of cancer at all, to my knowledge, so we don’t know. But just logically, they’re also exposed to higher radiation levels and the same exposure as flight attendants in terms of the radiation, in terms of the UV radiation. So I guess the answer is that we don’t know, but it’s a concern.

11:51 - Mythconception - do most birds really mate for life?

Mythconception - do most birds really mate for life?

with Georgia Mills

Birds have a reputation for being the most lovey-dovey animals, after all - most of them mate for life! Don't they? Georgia Mills has ruined the romance for all of us...

Georgia - However confusing, dramatic, or upsetting human relationships can be we can all take solace from that beautiful image of all the different species of lovebirds who stay true to each other forever and bond for life. Or do they?

Birds are unusual in that most of them do just have one partner. The most common pattern of mating in animals is called “polygyny,” and this is where one male has a relationship with two or more females. But many species of birds have a one on one relationship and we call this “monogamy.”

In fact, 90 percent of bird species are monogamous but this doesn’t always mean ‘till death do us part.’ Often this will just mean a pair will stay together for one breeding season to bring up their chicks before looking for a new partner. But there are some species like swans, geese, and cranes who do stay together for life. But are they true to each other? This is a bit more of a grey area. Because, you see, advances in genetics have shattered our illusions of feathered fidelity. Those birds have been playing away from the nests.

When scientists actually do genetic testing on a nest around 30 percent of the eggs in most species will not be related to the male lovebird. Those blue tits, herons and, unsurprisingly, shags have been out philandering while their partner isn’t looking.

And the ultimate adulterers are the superb fairy wrens. While they present the image of perfect familial devotion, 65 percent of their chicks will be from a different daddy. And this is because the females sneak off just before dawn to the territories of the sexiest males and then, well, ‘the early bird catches the sperm.’ And what female fairy wren could resist those bright blue males seductively dancing and presenting them with yellow flower petals.

All this debauchery shocked people when it first came to light, but there’s a good evolutionary reason for it. Females can only have so many eggs, so it’s a good idea to increase the genetic diversity of their broods so that at least some of them will survive. And, if you’re a male bird, it’s generally a good idea to have as many chicks as possible. And even so, there are still a small minority of bird species that, as far as we know, do mate with each other exclusively.

There are some other animals that do only mate with one partner their entire life but usually the reasons are less than romantic. Some very short-lived species simply don’t have the time, and for others mating is the last thing they ever do. Some species of male spider throw themselves into their special one’s jaws and get busy being eaten alive while they finish their romantic encounter. And, rather grotesquely, some species of reptiles, bees, and primates try and ensure their partner won’t mate with anyone else by gluing up the reproductive tract - it’s what's called a “mating plug.”

So, in summary, if you’re looking for inspiration on romantic relationships... don’t look too closely at the animal kingdom.

15:02 - Making better biofuels

Making better biofuels

with Dr Jason Hallett - Imperial College London

Petrol burned by cars accounts for 20% of man-made greenhouse gas emissions. So there’s been a big push in recent years to shift towards carbon-neutral “biofuels” by turning plant sugars into ethanol. But it’s important that doesn’t come at the cost of food production, so scientists want to tap into the sugars locked up in more complex molecules like the cellulose in wood. The stumbling block, though, was that present industrial processes couldn’t do this in an efficient or economically viable way. Now a London-based chemist has discovered a way to dissolve cellulose in a solvent called an ionic liquid, and stabilise wood-decaying enzymes from fungi so that they can work in that liquid and at very high temperatures to dramatically speed up the release of sugars from woody material. Chris Smith spoke with Jason Hallett from Imperial College London...

Jason - We would like to replace petrol with a biofuel like ethanol. The problem is that ethanol, at the moment, is made from sugar from sugar beets, or starch from corn and those are things that we eat. And so there’s a big ethical debate as to whether we should be taking food and turning it into fuels. What we have done is make biofuels and bioethanol from trees and this enables us to move our energy production off of agricultural land, and yet make sustainable fuels that won’t lead to CO2 emissions.

Chris - Why is it a challenge to make alcohol from things like trees? Are we not already able to do that?

Jason - We’re already able to do this, but the technology is very, very expensive. The most expensive part is the protein, or enzyme that breaks down cellulose to make sugars like glucose.

Chris - When you say cellulose, that’s wood right?

Jason - Yes. Cellulose is the main component in wood. Kind of a surprising fact, but trees are about 70 percent sugar. Roughly 50 percent of a tree is made up of cellulose which is a big polymer of glucose, sort of like starch, but not one that we can digest. Microbes, like fungus, are able to do this because they have special enzymes. Unfortunately, those proteins were evolved to not work very fast and so this whole process is incredibly slow, far too slow for us to make biofuels this way.

Chris - How have you tried to intervene and soup up the process?

Jason - What we did was we modified the surface of the protein using chemical techniques in order to make it much more stable. The second challenge that we had is that cellulose doesn’t dissolve in water. Now this is actually a good thing; if cellulose did dissolve in water then every time it rained all of the forest would dissolve. What we did is we dissolved the cellulose in the only medium that can do that, which is a liquid salt, sometimes called an “ionic liquids”, sometimes called a “molten salt.” This enabled us to put the cellulose into solution, but in order to get the protein to work in that environment we had to protect it and so we had to modify the surface of the protein so it could withstand high temperatures - temperatures above the boiling point of water. This made that cellulose to glucose reaction very very fast, which would enable us to make the biofuels much cheaper and much more quickly.

Chris - When you use this, how does it perform? What sorts of metrics do you get out of it?

Jason - On its natural substrate; two glucose molecules bound together and it chops them into two, we were able to increase the rate of that reaction by a factor of 30. But the far more interesting thing was that now we could take cellulose, which is a massive polymer of glucose, and we were able to break that down with one single enzyme, and in natural conditions this is impossible.

Chris - So how would it work then? People would dump what, their garden refuse - whatever into their green bin, it would come to a plant, and how would it then get turned into ethanol with this added to the process?

Jason - This would be a way of enabling what we call “a consolidated process.” So we’ve taken two steps and put them into one so you can use this ionic liquid or liquid salt to dissolve your green waste into a liquid form, put in the enzyme to break it down to sugars, and then the sugars go off for fermentation to make biofuels or bioplastics or whatever sort of renewable materials that we would want.

Chris - Beyond just biofuels, given that stabilising enzymes is a real challenge for other sorts of industries in lots of different contexts, could you take the learning from this and now apply it to maybe washing powder to make better biological washing powder? I mean, that’s just one example but you see where I’m going with that?

Jason - Yeah. And it’s actually, it’s a very good example. I was talking to one of the world’s leading manufacturers of washing powder about this technology just last month. It turns out that stability under the conditions that exist in a washing machine is a really big issue. And the enzymes that are used in washing powder tend to lose a lot of their activity very very quickly during the wash cycle. So yes, this could very easily turn into a solution to that problem as well.

The science of ROARING!

with Dr Jordan Raine - University of Sussex

What are non-verbal vocalisations, such as roars, actually for? Georgia Mills has been investigating...

Georgia - Roaring is the domain of the lion, and the tiger, and the T. Rex. But perhaps not something you’d readily associate with people.

But if you’ve watched a football game or an episode of Game of Thrones you will have experienced the mighty human roar… but what are roars actually for?

Jordan Raine is a Behavioural Ethologist from the University of Sussex and he’s interested in non-verbal communication like roaring...

Jordan - Available evidence suggests that these non-verbal vocalisations essentially communicate the same types of information and influence our perceptions and our behaviour in the same way as vocalisations do in non-human mammals where these vocalisations are, essentially, the primary form of communication and are a big factor in what determines animal’s access to resources, their reproductive success, and their chances of survival.

Georgia - But do humans, with our added luxury of verbal communications, still use roars in a similar way to our animal cousins? It was time to conduct an extremely loud study.

Jordan - In my paper, what I did was I got actors in training to immerse themselves in a battle or war scenario and to produce aggressive roars along with aggressive speech. And, essentially, the aim of what we were looking to find out was: is it the case that human roars communicate information about formidability, so our strength and our size, things that dictate our fighting ability? And do roars communicate information about these things in the same way that the roars and roar-like vocalisations in other mammals do?

Georgia - Jordan got some actors to come along and roar - here’s a clip…

Roar.

Georgia - Or yell an aggressive phrase like this one:

That’s enough, I’m coming for you.

Georgia - Our poor participants then had to guess if the person was stronger or weaker than them, and if they were shorter or taller…

Jordan - We found that listeners were pretty accurate at judging someone’s strength and someone’s size relative to one’s own. So, for example, listeners incorrectly judged vocalisers who were stronger than themselves as weaker on 18 percent of trials. And when they were judging vocalisers who were much stronger than them, that figure dropped to 6 percent.

Georgia - So why would linking a roar to someone’s size and strength be useful? Well, in the animal kingdom, creatures use this all the time as it can help avoid getting into a fight you’re pretty certain to lose. So if you here this…roar... and you sound like this...meow... you can act smart and run away and live to fight another day.

This way, grudge matches can be settled without actually having to enter a fight which could be dangerous to everyone involved, but animals will always try and trick the system.

Jordan - For example, the red deer is able to lower its larynx - its voice box - all the way down to its sternum and elongate it’s vocal tract, which is part of the vocal apparatus that provides cues to body size. And in our study in humans, what we found is that when male vocalisers roar they are much more likely to be perceived as stronger and taller than when the produce aggressive speech even though, obviously, their strength and their height are the same across those two stimuli.

Georgia - So roaring exaggerates the perceived strength of an individual. Back in our evolutionary history this probably came in handy when we were trying to scare off rival lovers or steal other people’s mammoths. But is roaring useful to us now?

Jordan - We’ve all heard the roars in battle scenes in Game of Thrones or Lord of the Rings, but humans don’t just roar in Hollywood films or TV dramas. Historical accounts have indicated that roars have been employed by soldiers in battle all the way throughout history from the Roman Army to the Red Army. And even now, the US National Parks Service recommends roaring as a defence strategy against bears, so it’s a useful weapon to have up your sleeve. I hope no-one ever needs to be in that situation where they have to defend themselves against a bear, but if you are in that situation then puff up your chest, make your arms wide, and definitely give as loud and as threatening a roar as you can.

Georgia - Can you do your best roar for me?

Jordan - I’ll give it a go. I’m a little bit under the weather but we’ll see what I can produce.

Roar!

Georgia - Ha ha. Amazing. I think you could definitely take me.

Jordan - We’ll see about that. Have you got one?

Georgia - Umm. Okay. I’ll move back so I don’t distort it.

Roar!

Jordan - I’m scared. I’m running away right now.

Georgia - I’ve never roared in an interview before so that’s a first.

Jordan - Well there you go - there’s a first time for everything.

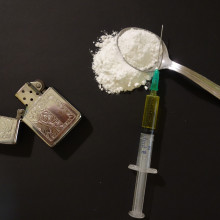

The opioid crisis

with Dr Bryan Roth - University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

In the US last year, more than 50,000 people died of opioid overdose. Georgia Mills spoke to pharmacologist Bryan Roth at the university of North Carolina Chapel Hill...

Bryan - Currently in the US we’re having a crisis of really catastrophic proportions. In the last year alone more than 50,000 people died of opiate overdoses and many hundreds of thousands or millions of people are currently dependent on opioids both prescription and illegal opioids. And to sort of put that in perspective, the number of people that died last year in the United States from opioid overdoses is roughly the same as the number of Americans who died in the entire Vietnam war, and the same as the number of Americans who died in the entire Korean war. So this is a huge huge problem.

Georgia - People are prescribed these for pain. Then what happens?

Bryan - Most people actually have no problem with them at all. But there is a significant portion of individuals that even after the first time they take a prescription opioid basically have a tremendous feeling of euphoria. I was at one time a full time psychiatrist and would frequently have patients who were opioid or heroin addicts as my patients, and the story they would tell invariably was after the first or second time they took a prescription opioid they basically felt like they had found what they were looking for their entire life in terms of the feeling of wellbeing and the euphoria that was attained.

As I said, this doesn’t occur with everybody, but when you have millions and millions of people taking these compounds, even if it occurs with only 5 or 10 percent of the patients, then you have hundreds of thousands to potentially millions of people who are at very high risk of ultimately abusing the medications and becoming dependent upon them.

Georgia - How does this eventually lead to death?

Bryan - Well, what happens typically is drugs like opioids lose their effectiveness in terms of producing the euphoria, relatively quickly actually. People will increase the dose and very quickly they can get to a point where the dose that is required to induce euphoria or to stave off symptoms of withdrawal from opioids after they become dependent gets very close to the dose that suppresses respiration. And death is typically due to suppression of respiration so people basically stop breathing and then they die within a few minutes.

Georgia - What is your lab doing to try and solve this problem?

Bryan - My lab has been studying opioids and the molecules that they bind to in the brain - they’re called “opioid receptors” - since 1983. And our idea is that if we can understand how these drugs interact with their targets in the brain, which are the receptors, then we might be able to make new medications that mimic the beneficial actions of opioids, reducing pain without the side effects.

Georgia - So you get all of the good and none of the bad. Is it the fact that it’s the way that it docks onto a cell in one place or does it have - this might be simplistic - but does it have one bit that causes the pain relief, one bit that causes the addiction, and if you could just get rid of that bit it would all be fine?

Bryan - That’s what a lot of scientists think. And we’re currently in the process of testing that notion that there is sort of one confirmation of the receptor which interacts with certain proteins which is responsible for relief of pain, and another sort of set of interactions which are responsible for the side effects. We can sort of break that down into chemical reactions inside the cell and then it’s relatively straightforward - I wouldn’t say it’s simple - but a relatively straightforward way then to design medications that sort of tickle one pathway and not the other. Then, of course, once we have them then we test them in mice and through multiple irritative cycles eventually hope to get these into humans for human testing.

Georgia - These are just sitting on the table waiting to get through the system really?

Bryan - Yes. Yeah, there are lots of safety things. We want to make sure that even though the drugs hit the receptors in the brain that we want them to hit that we want to make sure they don’t hit other receptors or have serious side effects that are not related to their known actions, and these things take time.

Georgia - Have you had people suggesting this maybe could do more harm than good?

Bryan - This is always the concern that when you make something new that hits opiate receptors that it may actually be more addictive than what you started out with. Heroin actually was made I think in Germany, but was initially used in the US to stave off dependence of morphine. So at that time in the US we had a number of people who had survived the Civil War that were morphine addicts and heroin was initially used to stop morphine addiction.

Georgia - Woops!

Bryan - It turned out to be more addictive than morphine. And so, as you can imagine, the regulatory people have a number of hurdles that these drugs need to go through to assess what’s called “addiction and dependence liability” before they can be tested in humans. And then, even in early human studies it’s possible to get a really good signal as to what their abuse potential will be. So I wouldn’t say we’re 100 percent confident, but certainly all the regulatory procedures and testing is in place to help to make sure that doesn’t occur again.

32:29 - What is addiction?

What is addiction?

with Dr Amy Milton, Cambridge University

What is addiction, and how does it work in the brain? Katie Haylor spoke to neuroscientist Amy Milton from the University of Cambridge...

Amy - So addiction, we normally think about in the context of drugs of abuse like opioids that we just heard about. In addiction, behaviour narrows very, very markedly to being really focused on drug seeking and drug taking behaviour and that’s to the exclusion of everything else. So people losing their jobs, their family, and so on. And the key characteristic of addiction is that there is a lot of control over that behaviour. So people are aware of the fact that these behaviours are hurting them, but they can’t do anything to stop doing it, and it’s a chronic and relapsing disorder. So people will often manage to get off drugs for a period of time but then they’re very at high risk of relapse for the rest of their lives actually.

Katie - Do we know how addictions work in the brain?

Amy - We have a pretty good idea. As you can imagine, for a complex mental health disorder there are lots of things that go wrong - there are a few key things though. One is that drugs of abuse massively increase the amount of dopamine within the brain, and dopamine is a really, really key chemical for learning about things that are motivationally relevant to you in your environment.

So we normally learn about rewards - natural rewards like food and mates and so on, with big increases in dopamine. Drugs of abuse increase dopamine massively more than natural rewards, so hundreds of times more. What this means is that the behaviours that lead to the drugs being obtained, are far more likely to be engaged in. There is a shift, very very quickly, because dopamine encourages this from goal directed behaviour - doing something because you want the outcome - to habitual behaviour where we just do it because that’s what we do in a particular environment.

Dopamine increases the influence that the environment has over behaviour, so cues in the environment that are predictive of drug rewards come to be far more attention grabbing and controlling of behaviour. And, the key clincher is that there is a loss of cognitive control mechanisms mediated by this area called the prefrontal cortex. Many drugs of abuse are very toxic to the prefrontal cortex, and people who tend to become addicted often have lower inhibitory control to start with and the drugs of abuse reduce that inhibitory control further. So that habit becomes a compulsive habit.

Katie - Can anything be addictive?

Amy - That’s a really good question. With drugs of abuse it’s very, very clear that there’s something unnatural in the body and that drugs of abuse hijack our natural reward system. When you’ve got a natural reward, so something like high fat, high sugar foods have been suggested as potentially addictive, gambling, other sorts of potentially behavioural addictions, it’s often harder to tell whether that’s a hijacking of a natural reward system, or it’s just a natural reward system itself. So sex addiction or food addiction is much, much harder to quantify and it really comes down to, is the behaviour having really adverse outcomes on the person who’s engaging in them.

Katie - So if someone is addicted to something, what happens if they don’t get their fix?

Amy - So they go into withdrawal, but there are at least two different types of withdrawal: physiological and psychological. Physiological withdrawal, it’s really obvious withdrawal signs. So if somebody stops using heroin for example and they have been using for a long time, they will show a particular set of symptoms like getting a really bad dose of flu, they often get quite bad diarrhoea, all these physical symptoms that are quite clearly there. What you get with psychological withdrawal is the system has been massively overstimulated for a really long period of time so the reward system has gotten used to being active at certain level. When the system like that is overstimulated, it becomes less sensitive. It's like the cells that are receiving the signal, kind of, put their hands over their ears. They are no longer listening unless they’re being shouted at.

So you take that drug away and you go back to normal physiological level of stimulation, those cells that are receiving the signal aren’t listening anymore. And so you get a rebound effect where people feel very depressed, they often feel very anxious. And the way of getting out of that state is by going and engaging in those drug seeking and drug taking behaviors again.

Chris - It was made as a joke at the Edinburgh festival by a comedian, but it sort of has a serious side to it which is this person said “why don’t you just take hundreds of drugs because then your body won’t know what to get addicted to”. But how do you, or how does your brain, make the association between a particular drug and you know you’re hooked on it?

Amy - All drugs of abuse, even though they all have very different actions in the brain, so nicotine, very different from heroin, very different from cocaine, all of them have this common action of increasing dopamine in a particular part of the brain called the nucleus accumbens. And every single drug that has abuse, that is addictive, has that effect, and you are very very good at learning in a completely unconscious way which environments or cues predict which particular outcomes and you can see variation. There are even experiments in rats showing that if you have rats who can self-administer cocaine or heroin in different environments, they tend to take heroin when they are in their home environment and they tend to take cocaine when they are out in a novel environment. So these environment really influence drug seeking and drug taking behavior as well in a quite a complicated way.

Chris - So if I fed someone pancakes, but also injected them with heroin without them realising it, would they form the addiction to pancakes so that they would then get the pleasure from the pancake because the reinforcement was there but they didn’t know it was heroin it was doing it, it was the pancake.

Amy - so I guess it would depend on how much experience they had with pancakes before. If they had experienced pancakes many times before and yet your pancakes are that much better, they will only seek out your pancakes and presumably you’ll give them heroin again. If they had not experienced pancakes before, then they may associate that euphoric rush with the taste of the pancakes. There may be a little bit of carry over to subsequent pancake experiences even without the heroin but i think they would very rapidly extinguish and just go back to normal pancake eating habits, unless they were getting your heroin laced pancakes again.

Katie - For someone who does have an addiction, what kinds of treatments are there?

Amy - So we are very limited in the treatments that we have at the moment. There are treatments that exist, like the 12 step programme, which don’t necessarily have a strong scientific understanding, but if they work for certain people then they should use them. But other drugs of abuse, like cocaine, there are no approved treatments. For other drugs like nicotine or heroin, we’re looking at replacement therapy as the alternative. For drugs like alcohol, there’s antabuse. But quite often people will stop using antabuse which produces hangover like symptoms rapidly when somebody drinks alcohol. What tends to happen is people will stop using the antabuse and carry on using the alcohol. So there is a real clinical treatment need and a real push for new treatment development, which is one of the things that my lab and other labs here in Cambridge are doing.

40:33 - Early warning signs of gambling addiction

Early warning signs of gambling addiction

with Dr Raian Ali - Bournemouth University

Gambling is recognised as a serious addiction. For the 2018 World Cup, the amount of money spent on gambling is expected to hit £2.5 billion in the UK, and over 400,000 of us are identified as problem gamblers. People are also concerned with the rise of problematic use of social media and video games. But unlike substances such as nicotine or heroin, the very same mechanisms that are used to make online platforms so addictive could be used to warn people that they are showing signs of becoming addicted and help them to regulate their use. At the moment this is not happening though. Georgia spoke to Raian Ali, from the the Digital Addiction Research Group at Bournemouth University...

Raian - Our main argument or main statement is that technology is more intelligent than alcohol and tobacco because it can measure the usage, it can sense when you could be using them in an addictive style or problematic style and can show you a message, make you more informed about that usage.

Georgia - What kind of techniques then are games and social media using to try and keep people coming?

Raian - Say, for example, SnapChat as a social media: you have events that are only temporarily available, so you have to go check SnapChat otherwise you wouldn’t get access to that snaps. That’s called “scarcity”, so it’s only available for a limited amount and a limited period of time. There are other techniques like reciprocity. If you do something the social network will reward you for that; for example if you interact via the social networks, the social network will know more about you and will customise the content to you to fit your interests. Social media in general: let's say for users, there is the need of people to belong as well - to be a member of a group. So basically, they process their data, they know their interests and they show them interesting news in a way - they personalise that.

Georgia - Is this something to do with like when you get a notification that gives you a little dopamine hit?

Raian - The pull to refresh, which is a feature found in most of the digital media nowadays, especially when you are using a mobile phone, is in a way using a gambling technique like when you have the roulette thing. And you just press a button and you wait for the roulette and then after that you may win and you may lose. So that sort of surprise element, that sort of uncertainty and the reward which may come after that is, in a way, similar to gambling, which is a technique now used in social media somehow.

Georgia - Right. So you spin the wheel, you might get a friend request (yah) or you might get nothing?

Raian - Exactly. And there is also a common rule on social media now that no news is not good news, so social media all the time strive to show you something. Whenever you go there you see a notification, you see something new even if it is not that relevant to you. Because people would like to see something there even if it is irrelevant.

Georgia - Let’s talk about gambling because it’s the World Cup at the moment so a lot of people have sometimes harmless bets on matches, but for other people this is a very very serious problem. So how much gambling is there and how does that become an addiction?

Raian - I think for the online gambling there’s an interesting fact now that these sites know a lot about people, so they know exactly what a person is doing there. They collect a lot of data about them, they personalise offers to them, and they also make profiles for them. So likely the gambling sites are more intelligent than the traditional gambling and they use AI techniques - artificial intelligence techniques to protect a gambler’s behaviour. That could exacerbate the problem of gambling addiction. What we are saying is that these data they collect about people to protect their gambling behaviour and to customise offers to them or promotion to them can be equally useful for responsible gambling. However, currently, these data are not being made available for responsible gambling application software, they are only being used for marketing and personalisation.

Georgia - So this data that’s coming in from people gambling away online could be used to help people stop, but at the moment it’s being used to keep people there?

Raian - Absolutely. To give you a metaphor: if somebody’s driving a car and overspeeding, it doesn’t make sense to tell them about their behaviour after the make the accident. So what we are advocating is that these gambling sites should stream this data in real time, in timely fashion to their mentor, to another software, to their therapist so that they can take action before the problem gambling happens - before the addiction happens.

Georgia - Where’s the incentive, other than just the desire to bring about social good, but where’s the incentive for gambling companies to do this because if people stop gambling they lose money?

Raian - There are a lot of court cases now about gambling companies failing to practice their duty of care. There are fines imposed on them because they fail to detect addictive gamblers. It’s for the benefit of both society and the gambling company to detect those problematic cases. And the majority of gamblers are not really problem gamblers so the profit of the company wouldn’t be hugely affected by detecting problem gamblers in the early stages and keep the gambling to an acceptable level.

Georgia - In terms of duty of care, gambling comes under a different law from a video game, but recently a trend in video games is to have what’s called these “microtransactions.” So how is that changing the landscape of how you see people’s video game use?

Raian - There are hypothesis whether there is a transitional relationship between video gaming and gambling. And whether people who play virtual gambling, like with virtual points and so on, can become gamblers. There isn’t a lot of evidence of that transitional relation and I think the gambling authorities are putting this under investigation now to see whether normalising gambling through video games can lead to actual gambling. There isn’t a lot of evidence about that.

Georgia - Something I’ve heard about, these things called loot boxes. These are things you often pay real money for and get a sort of mystery item or set of items within a game, so would that not qualify as actual gambling?

Raian - Personally, I think that raises a lot of ethical issues. Whether it is gambling or not can be debated. But it’s like pushing the kids basically to push their parents to pay money to buy the next release of the game. That raises a lot of ethical issues of the tech company...

47:38 - Are video games addictive?

Are video games addictive?

with Dr Louise Theodosiou - Royal College of Psychiatrists, UK

The World Health Organisation recently recognised “gaming disorder” as a mental health condition. So is this based on sound science, or are we turning an everyday behaviour into a disease, or providing parents of spoilt children with an excuse? Gaming is a multi billion dollar industry with a bigger turnover than Hollywood, and it’s enjoyed by millions of children and adults. So what’s the answer? Louise Theodosiou is a Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, working with the Royal College of Psychiatrists in the UK...

Louise - As we heard before, gambling is about a narrowing of behaviour. And what gaming disorder from the World Health Organisation talks about is about people who have a pattern of gaming where they’re losing control of their gaming. They’re giving increased priority to gaming and carrying on gaming despite negative consequences, and one of the things that WHO emphasises is the fact that, actually, there’s an impact on people’s lives. Kids are struggling with their education, they’re not maintaining enough sleep, there is an impact on how healthy they are and their social interactions in the real world are suffering. So it’s about that impact on life and about the fact that this is carrying on for over 12 months, so we’re looking to see that impact and that narrowing of behaviour.

Chris - That seems to tick most of the boxes highlighted by Amy Milton a few minutes ago on what would be classified as an addiction.

Louise - I would agree that it does. And I think one of the brilliant things about the announcement is that we’re now starting to have a clear definition that will mean that we can focus our research more clearly. As I’m sure you’re aware, the American diagnostic system has had a slightly different definition, but a very similar condition: internet gaming, as an area of concern for about five years. And if we look at the literature we can see that there has been an increasing body of literature developing for almost 20 years now. So that situation of problematic internet use, and problematic gaming use has been around and is gathering momentum and I think that’s what makes this announcement so important.

Chris - Bryan Roth, when we opened this previous part of the programme said that, for millions of people, painkillers are a wonderful thing that have helped them over a painful episode and they’re only an issue for a small minority. In my introduction to you I pointed out that millions of adults and children use gaming as a diversion, as almost therapy. It’s a stimulus, it’s a distraction, it’s a way to relax and they do it quite healthily. So can we tell who are going to be the people for whom it is going to become a problem?

Louise - I think that’s an excellent question. And just to emphasise, yes, I think gaming can be very positive. I think it can actually be something that in a very short and very controlled way can really be a socially beneficial thing for children and I think the internet overall has huge benefits for mental health practice, and it’s about finding that balance, it’s about that moderation and, as you’ve said, lots of people benefit from painkillers. Lots of people benefit from gaming but there probably are doing it in the context of lots of other experiences at the same time, and it is about that group of people who lose control of their gaming.

And yes, while we are still needing to do more research, there do seem to be some of the same brain areas that were identified in the piece about addiction, that study areas that we need to look at more in people who have gaming difficulties. And there does seem to be a connection with people who, for example, who are suffering from depression and maybe have developmental conditions such as ADHD and some of the anxiety conditions.

So the fantastic thing is that now we’ve got this definition of “gaming disorder” we can start to narrow down our studies and to identify the groups of people more clearly, and identify how we can recognise them early. Because that’s the other good thing about having this definition of gaming disorder is by having a definition of depression in that same diagnostic classification, people like myself can help teachers and other people look at kids who might be at risk of getting depression, we can start to do the same thing now with gaming disorder.

Chris - Are there any sort of broad categories that the people who are susceptible tend to fall into: more boys than girls; teenagers than younger children? Do you have any idea?

Louise - What’s interesting is that there does seem to be slightly more boys than girls. But then what’s interesting if you look at the studies, in a number of studies boys are overrepresented. What’s also interesting is that a number of the studies have concentrated on pre-teens, teens, and university students, and yet a lot of people who may be struggling with their gaming may actually be older than that. So I think that’s something else we probably need to look at overall is to check that everybody who can potentially be affected is actually included in those research studies.

Chris - If we follow up these people; say we identify someone who clearly has a big problem, how do we help them?

Louise - What we need to do is we need to, I suppose, first of all make sure that there is that opportunity to have that dialogue with people. We need there to be more information; that’s why programmes like this are so important so that families, loved ones, carers can be identifying that people maybe are at risk because of their gaming. Then what we need to do is we need to make sure that people know who to talk to - speak to your GP. What we know is because of that connection with some of the mental health needs that I was talking about before, GPs can be really useful in telling you what difficulties in terms of knowing what difficulties you might have. And we also need to remember that there’s a lot of really good practical ways of addressing all mental health problems and that those common things will apply. You know, things about thinking about your anxiety, looking at what’s actually going on, looking at other strategies, interacting with other people, leaving the house. All of these really good sense, mental health, wellbeing things that we’re doing for all sorts of other conditions can also be useful in this condition.

Chris - Do you think this is a proportional label because, strictly speaking, the number of people who die of video gaming problems is not high is it compared with other drugs?

Louise - The internet has a potential to have a huge impact on people’s lives: sleeping, reversed sleep cycles, people not attending to their basic health care needs. If you fall and break you leg while you’re playing football you’re not going to be able to carry on. People can potentially damage their health while online and might not realise it in the same way, so I do think there’s a concern that we need to understand.

54:20 - Why do humans get bored?

Why do humans get bored?

Adam - Having the same routine every day can make someone restless and bored. What about eating the same food day in, day out or being at a doctor’s office when your mobile phone runs out of battery? Almost everyone suffers from boredom in the course of their lives, but why do we get bored?

On the forum, Melvin suggested that it’s quite clear that boredom is a necessity for any development or improvement in our lives. Mr. Toad, from the Wind in the Willows, would still be comfortable with his horse and cart if he didn’t get bored and invented a sports car and eventually a plane.

I asked Professor Brian Little from the University of Cambridge, who’s an expert on human personality and wellbeing, to weigh in on the topic of boredom…

Brian - When individuals actively engage in pursuing a goal, different emotions will inform them of how these pursuits are proceeding. For example, enjoyment typically reflects goal attainment, anxiety signals threat, and anger the blocking of a valued pursuit.

Boredom is distinctive as an emotion because it signals that a current activity or goal pursuit has lost its meaning and significance - it no longer engages us. Boredom provides physiological and psychological motivation to search for new activities or pursue different projects.

Adam - But boredom is anything but boring and can prove to be beneficial…

Brian - The evolutionary significance of boredom is that it created the motivation for exploration. Whether it is moving to new locations, trying out new foods, or seeking new mates, boredom expanded the repertoire of human possibilities and the creation of future options beyond the boring present. Some of these would prove to have adaptive significance for the species, while others would lead to dead ends.

Personality researchers have a distinctive way of looking at boredom. They examine the way in which each person is like all other people, some other people, and like no other person. All of us experience boredom at times, but some individuals are more boredom prone than others. Extroverts are more boredom prone than introverts and are motivated to seek out stimulation from other pursuits and engaging projects.

And like no other person, you may have your idiosyncratic boredom triggers. If this commentary has your eyes drooping and your engagement flagging, let it serve as a stimulant for you to explore exciting alternatives elsewhere. Quickly.

Adam - Thank you Professor Brian Little for that entertaining answer. Next week we will be picking your brain with this question from Tuomo Seppala:

Does your brain respond differently when you’re listening to an audiobook compared when you’re reading a book? And does this affect how much details you can remember?

Comments

Add a comment