This week, we're casting our eyes towards the brightest and largest object in our night sky: the Moon. As India becomes the 4th nation to achieve a successful soft landing on our only natural sateillite, we saw a fantastic opportunity to chart the history of how the Moon was formed and the many billions worth of missions invested in finding out more about it...

In this episode

01:02 - Where did the Moon come from?

Where did the Moon come from?

Dana Mackenzie

Chris Smith spoke with science writer Dana Mackenzie, the author of 'The Big Splat, or How Our Moon Came to Be.'

Dana - The Moon is one of the most amazing places in the solar system. It's much larger compared to our planet than any other moon in the solar system. Earth's moon is about one 80th the mass of earth, comparable in size to North America in terms of land area. And so this suggests that our moon has a very special origin story. Another thing that I think is really cool about our moon, we're really a double planet. Both of the planets go around each other. So if you are an alien, you probably wouldn't say earth is the third planet. You'd say the Earth Moon system is the third planet from the sun.

Chris - You mentioned that it must have some kind of exciting origin because the Moon is so big.

Dana - This was a mystery for a very long time. And it's finally been resolved to the satisfaction of most lunar scientists. So the current accepted theory is that the Moon was created by a giant impact between earth and another planet. And this impact actually destroyed that planet. It basically liquified it and smeared it around the Earth in a ring. And then the debris coalesced over a pretty short period of time to form the moon. And so this giant impact theory was proposed in the 1970s, became accepted in the 1980s at first, considered really outlandish, but you have to realise that the early solar system was a really chaotic and violent place. And we see evidence of these sorts of impacts all over the place in the solar system. For example, we see the planet Uranus is tipped over on its side. What did that? Probably a giant impact. And the same for our moon. So the moon really has a lot to tell us not only about our origins, but also about what the solar system was like early in its history.

Chris - If the Moon was born from an impact between the early Earth and some other impact tour, does that mean it's made of the same stuff, effectively, that we are? Do we already know what's on the Moon? And we know the earth is replete with all kinds of exciting resources and therefore we can be reasonably sure the same thing is lurking up there waiting for us.

Dana - Well, that's a great question. And actually it's subtle because there are some ways in which the Moon is similar and some ways in which it's different. This giant impact for one thing would have boiled away elements that have a low melting point. So-called volatile elements are less common on the moon. And also, in theory, this is also why the Moon is vastly drier and there's virtually no water on the moon. And this was actually considered one of the main reasons for accepting the theory. Now, since I wrote my book, we've actually discovered that there is water on the Moon in small amounts, but perhaps in amounts that we can use. And it's located in the lunar poles, particularly the South Pole, where you have permanently shadowed craters. So now one of the big questions that the current missions want to address is how much ice is there - what form is it in? Is it mixed in with the dirt or is it more pure ice and how can we get it out? And that's one of the reasons why so many countries are now sending spacecraft there to answer these questions.

Chris - And is the reason they're focusing on the South pole of the Moon is purely because it's always in sunshine? Or is there another motivation for why they want to head down there? They're all going south. Why is that?

Dana - The main motivation is that the known deposits of water ice are the South Pole. Smaller deposits may be at the North Pole. There's a mission called LCROSS that deliberately crashed into the moon in 2010 or so in order to blow up a plume of debris so that they could see what was in the debris. And sure enough, they spotted water ice, water molecules. So we know that the water is there. The reason it's probably there is because, as you mentioned, permanently sunlit areas. But it's the permanently shadowed areas that collect the ice. They're so cold, they're colder than even outer space right now. So these are the areas where the water gets trapped and can't get out. Coincidentally, there are also regions of almost perpetual sunshine near the South Pole where you have mountains. There's one mountain which is almost in perpetual sunlight. Now you won't find water there, but it'd be a great place to build a base. So yes, that is useful as well. You could build your base on that mountain and then have your mining operation down in the craters.

06:18 - Lunar landings: India at the Moon's south pole

Lunar landings: India at the Moon's south pole

Richard Hollingham, Space Boffins

Many nations, of course, are still interested in the Moon. Last week, we reported on Russia’s first lunar mission in decades. It ended in failure after its craft crashed into the Moon’s surface. But there’s been much happier news for India - which has just made history becoming the first nation to land near the Moon's south pole. Chris spoke with science journalist, author and BBC presenter, Richard Hollingham. He's also the host of the Space Boffins Podcast...

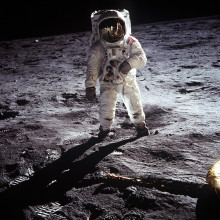

Richard - Remarkably, the first landing on the Moon was in 1959. It was the Soviet Union. Luna 2 crashed into the Moon in 1959. The first soft landing on the Moon - so coming down gently, which is what we saw with the Indian lander - was Luna 9. Again, the Soviet Union in 1966. Today, Russia would say they were Russian missions - they were not. They were Soviet missions. And in fact, the man behind them was Ukrainian: Sergei Korolev. The Soviet Union seemed to have the edge until about the mid sixties when you started seeing the Apollo missions. And we've heard in recent days about how the far side of the Moon is sort of broken up; mountainous and cratered - very different to what we see in the night sky. And that first became apparent when astronauts looked down on the Moon for the first time in December 1968, on Apollo 8. And I actually have been fortunate enough to interview the commander of that mission, Frank Borman. Like a lot of these people, he still gets emotional when he describes how broken up, how extraordinary this area of the Moon looks. And then, as you mentioned, Apollo 11. The last human stepped on the moon in December 1972. That was Apollo 17. And now, suddenly, We're getting back into this excitement about the Moon with the Chinese rover in 2019. And now the Indian rover, the fourth nation to soft land on the Moon.

Chris - And what's underpinning all that? Suddenly it's as though there's a rush of interest. Why now?

Richard - Well, sadly, the world is not run by scientists and things are not done always for scientific objectives. There is a political element to this, as you might well imagine. There is also fundamentally a taxpayer that foots the bill for these sorts of things. So, as you heard, there's lots of scientific imperatives to go back to the Moon. But it's also about the future of humanity. It's about moving beyond the earth. And so you could say we landed on the Moon too soon in the sixties because it was an absolute race to get there - purely politically motivated. And then the science came along after that. So now there's the science, but there's also politics. But there's also something bigger than that, which is using the Moon as a stepping stone to exploration beyond. And perhaps now we're doing things in the right order at the right time.

Chris - Why are India and China really thrusting ahead on this? Do they see that as their goal to have first past the post advantage? Let's get there first and secure that as the launchpad for the next big thing.

Richard - I can't speak for China, but I would say there's certainly a political element to this. There was a political element to Russia suddenly launching this mission, Luna 25, which had been originally planned for two years ago. So there was a political element to that. Of course, there's scientific cooperation on top of that. I think what's remarkable about the Indian launcher is that it's the new way of doing things in space. It's done so much cheaper. They've done it quickly. It's maybe a new way to do this. And in that respect, India is definitely in the lead here. But it will be really interesting. I would put my money on the US putting astronauts first on the Moon next, but China won't be far behind.

Chris - And just briefly on that last point, where are we on the timeline? Because have they not suffered a bit of a setback in terms of when they originally planned to put people back on the Moon? Is there going to be a delay?

Richard - We'll have Artemis 2, which will be the mission around the Moon. That will either happen in 2024 or 2025. The problem with landing people on the Moon is the lander. That's being provided by SpaceX, and it's looking like it's behind schedule. So it's going to be by 2030. But I wouldn't want to say sooner than that necessarily.

Chris - You're obviously not a betting man, Richard, thanks very much.

12:09 - Which countries lead the race to return to the Moon?

Which countries lead the race to return to the Moon?

Sajjan Gohel, LSE & Isabel Hilton & Scott Lucas, University College Dublin

Who are the runners and riders in the new Lunar race? Rhys James reports...

Rhys - On the 23rd of August, India announced its arrival as a space superpower, when the Chandrayaan-3 lander touched down on the lunar surface. It means that India is the first country to successfully land a craft near the Moon's South Pole. The nation's prime Minister Narendra Modi was seen grinning and waving a small Indian flag as Chandrayaan-3 made history. 'India is now on the moon', he told mission control, but what might that mean for the country and its space rivals? I asked Sajjan Gohel, who's a visiting teacher at the London School of Economics and Political Science and host of the NATO Deep Dive podcast to explain the significance of India's soft lunar landing.

Sajjan - India has become the first country to successfully land a spacecraft near the south Pole of the moon. It is a historic moment. This was a cost-effective moon landing, substantially cheaper than the ones conducted by the US, China, and Russia. India was using rockets much less powerful than the US. This was something that was part of a long journey for India's space research organisation, ISRO. And you are now seeing the culmination of that.

Rhys - And how much catching up has India had to do Sajjan? You mentioned that India is competing with these other superpowers, Russia, the United States and China.

Sajjan - Well, India's had a space program for many decades, but it didn't really develop properly until the last 15 years. India has always been viewed by the world in many ways as a junior space fairing state. If India can succeed where others have failed, such as Russia with their Lunar 25 spacecraft crashing into the moon surface, it then signals a new pecking order in space. And certainly it will create the perception of more competition in space, especially with China having launched in May a three person crew, which intends to orbit a space station and hopes to put astronauts on the moon before the end of the decade.

Rhys - What about India's cooperation with its allies? Presumably the likes of Japan, the US and Australia, which along with India make up the Quad Military Alliance will be absolutely delighted with this.

Sajjan - In July, India became the 26th country to sign on to NASA's Artemis Accords, which are Washington's preferred principles for space exploration as more countries aim for the cosmos. So India is aligning more now with the United States when it comes to space exploration. And the US in itself is going to be very interested in what India will make from this recent craft landing on the moon. Because now being in the South Pole, the goal will be to investigate the presence of ice water, which could provide the building blocks of breathable oxygen, drinking water, and even rocket fuel.

Rhys - And does this represent a challenge directly to Beijing? We know obviously China is India's greatest Asian rival, and the nations have enjoyed a turbulent or fractious relationship in recent years.

Sajjan - Certainly it is going to create more competition between India and China. There should be no doubt about that. It will only intensify as the spacecraft of India's landed on the moon, you had the leaders of India and China in Johannesburg, South Africa for the BRICS summit where there were disagreements over BRICS expansion. So those issues are there. The border disputes between India and China continue. And now space exploration is probably yet another example of rivalries that will emerge between India and China.

Rhys - Sajjan Gohel. Now, as Sajjan was just mentioning, India's greatest rival is China, which is pursuing its own ambitious space program. But why exactly is the country's president, Xi Jinping, interested in the moon? I've been speaking to the China expert Isabel Hilton.

Isabel - China started quite late really, but it sent its first satellite into orbit in 1970. And of course the US had already landed an astronaut on the moon by then. But Beijing has put a lot of effort into it, particularly under Xi Jinping, but also in the decade before Xi Jinping. So they first landed on the moon, they landed a rover on the moon in 2013. They were only the third country to manage that. And Xi Jinping has repeatedly said that it's part of what he calls the China dream to make China a big space power. And he has been spending pretty heavily on it since they scored another first by mapping the dark side of the moon. And again, in 2020 they successfully collected rock samples from the moon.

Rhys - And you talk of that Chinese dream of Xi Jinping's. Is there an element of the Chinese politburo that wants to put boots on the moon like the US did in the 1960s?

Isabel - Oh, yes. That has definitely been announced. And I think that a lot of the work that's going on is to do with a further dream, which is to establish a permanent station on the moon. At some point in some capacity. China already has a space station and there is some concern that when the International Space Station is due to retire in 2030, that would leave China holding the reins, if you like, of the only functioning space station. And there is a sense that the moon is part of this desire to establish a kind of permanent presence in space from which China could seek to dominate and military technologies, space-based military technologies, or in dominating the facilities denying access if it chose to. It's a very powerful weapon.

Rhys - Is that ambition part of its geopolitical competition with the United States? Do you think that very much feeds into what Beijing is attempting to do?

Isabel - Undoubtedly. Who does China see as the power that could inhibit its rise, slow its rise, stop its rise. And you know, this is very explicit on both sides. And the United States does want to slow China's technological advancement and China has determined that it will match up to the United States and surpass it in the end. That is what the image of China as a dominant power entails. So space and the moon are very much part of that, in addition to the importance of being in space for communications technologies and for military purposes. If you look at the payloads of Chinese rockets, they're far more military than they are civil.

Rhys - Isabelle Hilton there. So should the US, which remains the only nation to successfully land humans on the moon, be concerned by the recent advances made by Beijing and now New Delhi. Scott Lucas is a professor of American studies at the Clinton Institute at University College Dublin.

Scott - It was the first country to reach the moon, still has the capability to go farther. The Artemis program has the committee goal of returning to the moon for the first time in more than 50 years, In 2024. The US has been one of the leading forces behind the International Space Station, even though that's going to be decommissioned in 2030. And the United States is still a leading force in terms of the military uses of space under the umbrella of space command. But I think more importantly, just the amount of missile and rocket development that they continue to pursue.

Rhys - I wanted to come onto that, because obviously the former president Donald Trump had some interesting ideas, not least the launch of the Space Force. Was that a vanity project or was that a realistic proposition, this idea of creating a military force in space?

Scott - You know space force sounded to me like a Saturday morning kid show, and I'm afraid it did to a lot of professionals that were out there as well. I mean, the US military has been involved in terms of space as the next arena of possible confrontation. You may remember going back to the 1980s with Ronald Reagan's Star Wars program in terms of using lasers to knock down incoming missiles. But what Trump did at the same time that he was reducing the funding for space and lunar exploration for environmental programmes, was like this big shiny military programme which he always liked to hook himself up to, with the idea of space tacked onto it.

Rhys - What role can private enterprise play in space and lunar exploration? We know that America's billionaires have all been getting in on the act. Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos...

Scott - It's not really the Musk and the Bezos that I'm looking to. It's the question of the myriad of companies, the myriad of engineering firms, the myriads of firms involved in physics, the myriads of firms involved in geology, involved in other sectors in terms of where you're going to get the industrial manufacturing developments, as well as the movement towards, for example, a green economy, which is gonna pivot in part in terms of what we can do in space, not for the benefit of sending a few people up there to go out and back on a high cost flight, but in terms of sustainable projects that are gonna last over the long term.

Rhys - That was Scott Lucas. So with the new and old kids on the block scrambling to explore the moon and survey its resources, I suppose the next logical question that we need to ask is, can any nation actually lay claim to it? Back to you, Chris.

21:52 - Lunar laws: can anyone own the Moon?

Lunar laws: can anyone own the Moon?

Michelle Hanlon, University of Mississippi

Can any nation - or commercial enterprise - lay claim to the Moon? Chris spoke with Michelle Hanlon, executive director at the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi.

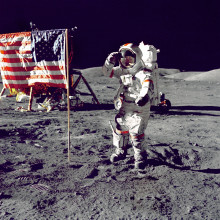

Michelle - Unlike what people may think - that space is somehow some wild west, and if you get out there, you can evade all laws - I'm sorry to say that laws will follow you into space. We actually have an outer space treaty, which was negotiated during the first space race in the 1950's and 60's, which has an article in it which says that no nation can claim territory on the Moon. So when the United States planted their flag on the moon in the Apollo missions, it wasn't staking a claim. It was simply saying 'We were here.' And so it's a very powerful provision of a treaty to which Russia, China, India and the United States are all parties to. So those nations can't go up and say, 'this is mine, you can't come in.' As lawyers, we like to interpret things. There's some questions about whether that applies to individuals and people argue differently about whether Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos can claim property on the moon or anybody else for that matter. But that's something that's still under interpretation.

Chris - So other than the technological constraints, what would stop a billionaire from going out there and then hammering a flag in and saying, 'I own that bit.'

Michelle - Absolutely nothing. There's no question. If somebody makes it to the Moon before one of these countries that is bound by this treaty, they can make any kind of claim they want. The question is, what is the value? We're a long way away from anybody being able to go to the Moon and saying, 'This is mine. Don't come in' and survive. They need to be tethered to a country and that country will hopefully reign them in.

Chris - What does that mean in terms of exploitation, though? You could go to the Moon and not say you own it, but you could still remove stuff. Say, for example, some kind of lucrative raw material or some kind of infrastructure were placed there, the person doesn't have to own the patch of the Moon to have that there, and they could nevertheless make money from it. So is that covered in the provisions of the treaty.

Michelle - So that is really interesting because that is a question of interpretation of the treaty. The United States announced in 2015, President Obama signed a law that says, we interpret the treaty to say anybody - a country or a nation, an individual, a company - can extract a resource and then do whatever they want with it. They can do scientific analysis, they can sell it. As part of the Artemis Accords, which are an agreement among nations about how they're going to act in space, a sort of follow up to the outer space treaty, those nations, only 28 of them have signed on to the Artemis Accords, all say, 'yes, you can extract the resource and do whatever you want with it. And, incidentally, India is a signatory of the Artemis Accords, as was mentioned before, and China is not.

Chris - And if someone goes and decides to transgress these rules, notwithstanding what you said about them being associated with a country, but just say they did. Has the treaty got teeth that mean it could do something about that? Or would we just have to stand on the sidelines and say, 'well, that's jolly unspiriting of you.'

Michelle - That is a great way to put it. And, unfortunately, in public international law, not a lot of treaties have teeth. Hence, we're witnessing the Russian invasion of Ukraine. There is nothing that we can do. We can't send up our Space Force. And we certainly don't want that to happen anyway. We really have to work now from the ground up to try and make sure that doesn't happen because it's going to be a lot more difficult to deal with if it does happen.

Chris - I was so pleased when we heard you were going to come on the programme because I was amazed that there's a big enough field for it to support a research centre and so on. Looking at this very topic, is this a rapidly growing and emerging area of international law?

Michelle - It's incredible. Space needs lawyers like you wouldn't believe. If you think about it, we have these nice rules which say you can't claim property in space, but we have this rule which seems to contradict it, right? And then we have this idea of having due regard for each other. That's how we're supposed to deal with each other in space. And what does that mean? What we need lawyers for isn't to gum up the works and start suing each other because that would be a disaster. What we want lawyers for is to start making sure we all understand all this language the same way, and that we can try and start to create custom and build traditions and make sure people are doing things responsibly and sustainably. And, incidentally, our centre here in Mississippi has grown. We used to have just three students, now we have more than 40. This is going to be big business, especially when you think about space tourism and all of the things we do with space satellites. So, if you have any interest, space needs you!

Chris - Does your jurisdiction, as it were, extend beyond the moon? Are you looking at everywhere in the solar system, including Mars?

Michelle - Absolutely. We are all going to be exploring all of space and as humans, hopefully, we will have the same code of honour as we do so.

Comments

Add a comment