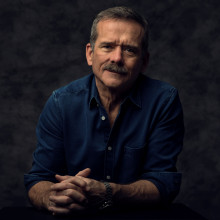

Titans of Science: Chris Hadfield

This episode marks the return of Titans of Science: full of in depth interviews with some of science’s greats. To start us off, the astronaut and rockstar, Chris Hadfield. The conversation covers his upbringing in rural Canada, his time as an elite test pilot in the US military - the inspiration for his latest thriller novel ‘The Defector’ - and his multiple missions into space, culminating in a stint as commander of the International Space Station.

In this episode

Chris Hadfield: Early life

Chris Hadfield

Chris Hadfield was born in Sarnia in Canada on the 29th of August, 1959, and was raised on a corn farm in southern Ontario. On graduating high school in 1978, Hadfield joined the Canadian Armed Forces and spent two years at Royal Roads Military College. He then studied at the Royal Military College of Canada, where he received a degree in mechanical engineering. Hadfield spent a total of 25 years in the rural Canadian Air Force, and 21 years with the Canadian Space Agency and NASA. He became the first Canadian to perform a spacewalk, and in 2013 became the commander of the International Space Station. I hope you don't mind, Chris, if we cut straight to the chase. Before we chart how you got there, take us to those first moments. 2001. You're pulling yourself out of the Endeavour and there's nothing but your spacesuit separating you from the rest of the universe beyond Earth.

Chris - It's an amazing experience, partially because of what you just described, the actual physical nature of what's happening. You're wearing a cloth balloon around your body that is carrying a little tiny bubble of just enough oxygen to keep you alive. Like you've brought a little microcosm of the Earth itself up there with you so that it can nurture you like an infant in their mother's womb, just to be able to stay alive. But it's the personal side that is really prevalent in that I had been dreaming of being an astronaut since I could remember, and definitely since I was 9 or 10. And the real personification of being an astronaut is to go outside on a spacewalk like the people on the Moon or Buck Rogers in the comic books - he wasn't just sitting in his ship all the time. He was out there doing things. So to actually be chosen and then trained and trusted to go out on a spacewalk where it's another whole level of danger and individual responsibility, it's a very rare thing. So that day you had to depressurise, you have to think about what diet you've had. You're going to be locked inside this suit for 10 hours. You're jammed into a little airlock, and there's not room for two people to be lined up. One has to be pointed one way and the other, the other way. So you're like head to toe in there and you've got this other person's feet banging into the visor of your helmet. I was the first person out. So I opened the great big metal hatch, but by then all the air's gone out of the airlock. So even though it's a metallic thing that's happening, there's no sound deadly silent. And you push that hatch out of the way and what was very confining, dark, crowded, little space. And now suddenly the entire universe is right there magically through this hole. Imagine next time you're in a toilet stall. Imagine if when you open the door of your toilet stall, if you were standing on the top of Mount Everest and then you close the door again and you go, 'how can this be on the other side of that door when I was in this familiar small space?' But you grab onto the hatch with both hands and you worm your way through it, almost like deliberately giving birth to yourself. And now suddenly you're in a whole new place with the gigantic, brilliantly coloured, textured world beside you, and then the unfathomably, huge blackness of the universe all around. It's an amazing transition.

James - You describe it so emotively and you focus on the emotion in that description, but all the while you've got a job to do. So that's something you've got to keep as in control as possible

Chris - I don't know, when a world class ballerina takes the stage, what might she be thinking about? Because the technical skills are so high for a ballerina and they have a lifetime of practice and the physically punishing nature of what they're doing. But there's also the beautiful symphonic music and there's the artistry of what's going to happen, but then there's all the mechanics of each memorised dance step - and I think there's a parallel there. Or maybe to an Olympic athlete who's going to go through their gymnastic routine or run a race. So yeah, you are very much focused on the compulsories and all of the objectives. We don't go outside recreationally. And in our case, we were building the huge robot arm, the Canadarm, onto the International Space Station. I had trained for it for years, literally for five years. So you've got all of those steps in front of you, but the overwhelming nature of the spacewalk itself and the where you are and the wonderment that comes along with it, you almost have to shake yourself to get past that so that you can focus on the absolutely necessary minutia of why you're there.

James - That incredible achievement amongst others in your life are brief snapshots of a long journey. I wonder if we could circle back and you could take us back to rural Canada in the 1960s and your memories of your early years.

Chris - My parents are farmers. They both had a high school education. In fact, they met in high school and they were both raised by farmers. But my dad's brother, one Christmas, bought him a ride in an aeroplane. One of those things where you can go for a local ride. And my father decided that's better than farming. And so he became a pilot. And so I grew up in an environment which was a combination of hard necessary physical labour of being a farmer as well as flying because my dad had aeroplanes. But what really caught my imagination was science fiction. And I voraciously read comic books and then Arthur C. Clarke and Bradbury and Asimov and all the rest. But also science fact, because interspersed with my agricultural reality and the dreams of science fiction, Yuri Gagarin flew and then Al Shepard and then the Gemini program, and then there were people going to the moon, Apollo eight on Christmas Eve went around the moon. And then the buildup to Apollo 11 and the summer that I was just about to turn 10, Mike and Neil and Buzz went to the moon, and Neil and Buzz successfully landed on the surface and got out and walked around. And that combination of growing up, hard work, aviation showing that that was possible, the dreams of fiction and the reality of what other people were doing, all of that lay down the foundations upon which I decided I'm going to try and be a pilot, be a test pilot, be an astronaut, and maybe someday do some of those amazing adventures that I've been dreaming about.

James - Amazing. So it really was a formative experience because I was at risk, I thought, of a gross oversimplification, or perpetuating a romantic ideal when trying to chart your life story. Those events and then your choices to study science were all geared towards this ambition to go to space from such a young age.

Chris - I was practical about it though, James, from the beginning. I wasn't like, if I don't fly in space, I'm a loser. Because I was Canadian, we didn't even have astronauts, we had no rockets, we had no NASA, we didn't have a space agency at the time. So the odds, they weren't just bad, the odds were zero. By definition, I could not be an astronaut as a Canadian - it didn't exist. But I knew that the only thing you can count on is that things are going to change. So I thought, 'Hey, the United States didn't used to have astronauts either, and now they do. So give it a shot.' But at each stage, I tried to make choices that were something that I wanted to do. And if that was as far as I got, that'd be okay. Like, I'm going to set my mind to be an engineer because a lot of astronauts have an engineering background, and that's a good career and there's lots of jobs I can get as an engineer. And if I count on being a pilot, well one little bit of metal in your eye and you're never going to be a pilot, again. So you can't count on something that has such tight medical requirements. So I became an engineer in university, and then I joined Air Cadets, learned to fly, became a pilot, and then became a fighter pilot, the most demanding level of being a pilot. And then test pilot school, because, to me, that combination of flying and engineering and flying some of the best aeroplanes in the world, that was just great. I would've loved to just stay as a pilot my whole life. That's a good career as an airline pilot. My dad became an airline pilot eventually and my brothers in fact. But then to be a test pilot, that was like the crème de la crème for me, the combination of all of it. There are lots of great jobs; they're dangerous but, as a test pilot, and really as I was a test pilot, there was only one other job that I would've considered a real step up for me in opportunity. And that was when I went through the selection process and, on a fateful Saturday, just a few minutes after one o'clock in the afternoon, the president of the Canadian Space Agency called me and asked if I would like to be an astronaut.

10:17 - Chris Hadfield: Becoming an astronaut

Chris Hadfield: Becoming an astronaut

Chris Hadfield

James - I'm keen to mine your experiences as a pilot and your time in the Air Force, which you yourself have been mining for the inspiration of your current book. I'm sure everyone, including me, is endlessly fascinated by your exploits in space. But you had your fair share of excitement well before you ever started training to fly in a rocket ship. Was it the best possible preparation? Were there hairy moments that meant that when you did become an astronaut you were able to remain calm under pressure?

Chris - The reason that so many of the early astronauts had previously been test pilots is there's a great number of parallel skill sets. If you're trying to do something nobody's ever done before and not be panicked and to have depths of competence so that you're ready to face the unknown, that's what test pilots do for a living. And it's only a small subset of fighter pilots who qualify to become test pilots. Test pilot school is a year, it's like a PhD in flying and it's deeply theoretical, all into the fundamental control theory maths of how all it works. And so I loved flying, but I always thought, 'wow, yeah, this is great. But someday I'd like to walk on the moon. So yeah. So I'm gonna go be a test pilot.' And I just found it endlessly fascinating. And I've ended up, now I've flown, I guess, I don't know, a hundred different types of aeroplanes from great big ones to little tiny ones, single seat aeroplanes, lots of different fighters, the great C141, C5, 747, those types of aeroplanes. And so a multi-layered competence in flying all those different aeroplanes. What you eventually learn is that all aeroplanes are the same. Just have to figure out how to start this one and how it's going to try and kill me, and stay away from those areas where this aeroplane has bad habits. All of that was preparing me not just to be a good competent test pilot, but what it was really doing was laying a really wide foundation of the type of skills that I might need later when I'm going to fly spaceships built by different organisations. And eventually to learn to speak Russian, to fly as the pilot of a Russian rocket ship and a Russian spaceship. And to put all those skills together all at once. So no matter what went wrong, I could still be trusted to do the right thing.

James - You talked about the culmination of that application process, and you remember the call saying you were going to be accepted onto the space programme.

Chris - Yeah, my wife, as soon as she saw the expression on my face, she was doing cartwheels across the kitchen floor. Because it had been such a long road for both of us. And she realised this was one of those watershed moments in life where we have been climbing and climbing and climbing, and somehow we now are just on the other side of a thing that will never change. And that, that was a great moment in life.

James - When we spoke to Helen Sharman, the first Briton in space, she recalls the way she even heard about it was driving home in the car and listening to a radio advert 'astronaut wanted, no experience required.' What was your experience of actually even this occurring to you as a possibility?

Chris - Obviously I looked at the nations that had astronauts, initially the cosmonauts and the Americans from the Soviet Union from the United States. And I used their skills as some of the skills I thought that I might need to gather, even though Canada didn't have astronauts. But then at the start of the shuttle program, Canada built the big arm on the space shuttle. the Canadarm1. And because we provided the arm to the space shuttle, NASA said, 'we'll fly three Canadians in space. They'll be like guest scientists on board.' We called them payload specialists. But that meant that in 1983, Canada, we didn't have a space agency yet, but there was a national recruitment for astronauts. I wasn't ready, I didn't even apply. But a bunch of people applied and they hired six people. So three primes and three backups. And one of them flew in space about nine months later. His name's Marc Garneau. He had a PhD. He was a Navy officer, but there he was, he's like Helen Sharman, he saw this advert popped up and, uh, to be an astronaut. He applied, he got selected, immediately thrown into training, and nine months later he found himself in space. But what that did was it opened the door for a Canadian astronaut programme. And when the International Space Station started becoming a reality, NASA wanted Canadians to be part of the international component. And so we had another selection, but in this case, we weren't guest scientists, passengers, but we were going to become fully fledged, fully qualified crew members, maybe with the opportunity to even command the space station someday. And so it was a little different selection process, but it was that Canadian technology that then gave us a membership to fly our first people with someone else's programme and a developing mutual trust so that then Canadians could have an increased role onboard the International Space station. And that's continued right through to today with the international crew that's up there right now.

James - <affirmative> Then the arduous application process, the watershed moment you describe, and I'm sure you're going to tell me, that's when the hard work just began.

Chris - The process was agonising because they said send in your resume. You had to be a Canadian citizen, you had to be able to pass a class one physical, and you had to have at least an undergraduate degree. But I'm thinking, 'well, that'll whittle it down to about 5,000 people, you know, so how am I going to stand out?' So I, and there was no internet back then. This was in late '91, early '92. So I tried to put together the most thrillingly deep resume I possibly could, leaving no stone unturned as to all of the things that I'd done so far in life because I didn't know what they were looking for. And then I bound it in a document on the most expensive stationary I could buy. I thought, 'man, I'm trying to stand out from thousands of other people. I don't want to inadvertently get shifted to the bottom of the pile.' And then I hired a shipping company and I was all nervously tracking. And then you wait and you hope they phone you. And finally got a phone call saying, 'Hey, we'd like to interview', and you realise there's going to be more than one interview level. And so iit turned out there were 5,330 people applying. And so out of those, they whittled it down to 500. And they called, 'Hey, you're at the 500 level. We want you to do an in-person interview with an industrial psychologist.' So I did that. And then you're waiting for another call. And then they were down to 120 people and they called, and then they were down to 50 people. And now they brought us all up to centralised locations where there were 50 of us to do a more in-depth interview. And then we were down to the final 20. And they hadn't even told us how many they were going to hire. So it was months and months of an upset stomach because I was powerless and this was hugely important in my life. And I was trying to put my best foot forward, but I didn't even know what my best foot was supposed to look like. And so I found it very unsettling and uncertain. But that last final week with 20 of us where we had very detailed physicals and we did a press conference, I had no idea, but it was just so they'd see how we'd react publicly and we'd had to write a big essay, and we had a big panel interview. And finally after all of that is when I got that phone call and they hired four of us. And then we showed up for the big hoopla announcement day. And that's where the game was afoot. And now it really began. But really that was just table stakes to start the hard work of all the things that you actually need to know to be trusted to fly a spaceship.

James - At this point, does it begin to creep into your head the possibility that you're going to space? Or do you have to temper that still so much because there's so many hurdles still to overcome. Being accepted onto the programme by no means guarantees you're going to space.

Chris - You recognise that there are people who get very close to being selected as an astronaut. They don't fly in space. There are people who get that phone call, but for whatever reason, life rears its ugly head. You have an injury or, or it turned out they don't like who you are. And so you never can count on the fact that you're going to fly in space. And in fact, you learn, because of the many years of preparation, you learn to just the ultimate gratification deferred. And you cannot count on space flight to justify what you're doing. If you do, it'd be a torturous existence. If the only part I liked about being an astronaut was flying in space, I would've hated my life because I only flew in space for six months, and I was an astronaut for 21 years. So the vast majority of my life was preparation and training and study and supporting other flights. So you have to make that the daily joyful part of who you are. And then maybe at the end of it, you'll actually get to fly in space. And even the day of my first space launch, which was in '95, at Space Shuttle Atlantis. We'd already had a full dress rehearsal day. And we'd gone out and got into the ship. And so the day we're going to space, it's like 'well, the weather might be bad or the abort sites might be bad.'

James - Still, you're still not letting yourself believe?

Chris - No. And so we got in and it was a beautiful day in Florida, but in case you lose some of your engines on the way to space, you actually have to abort and land either in North Africa or in the South or in Spain. We keep abort sites over in Spain or North Africa. And the weather in Spain and North Africa was bad that day. So we got into the ship, we were ready to go, and we had to scrub. And so it was one more day of very realistic training. But finally on the 12th of November, 1995, even though it was a much worse weather day in Florida, but good enough, the engine's lit. And even then, you don't let yourself believe because you're not in space yet. And it is only after the rockets have done their job, they've accelerated you from 0 to Mach 25. You're, uh, you know, a hundred miles above the Earth, you're going five miles a second, and the engine shut off, main engine cutoff, and you're weightless. That's when you allow yourself to believe that you're an astronaut.

21:21 - Chris Hadfield: Commanding the International Space Station

Chris Hadfield: Commanding the International Space Station

Chris Hadfield

James - Your first space flight, you must be with other astronauts who've got some experience. So, are you teasing out hints from them as to when they think it's a go? And then, you know?

Chris - Sure. I flew with four other people on my first space flight, they were all American and they had all flown at least once before. I was part of the flight crew up on the flight deck. There were four of us flying the space shuttle; commander in the front left seat, and I was seated next to Jerry Ross and this was his fifth space flight. He eventually flew seven times in space. Whenever I didn't know what to do, I just did whatever Jerry was doing: 'What's Jerry doing? He knows what he's supposed to be doing at this point' and that was very helpful. But when we were sitting on the launch pad, five minutes before launch, you're laying on your back in your chair and I'm like, 'Oh, it's getting pretty close to launch!' I looked over and Jerry's right knee started bobbing up and down nervously. I'm sure he didn't even notice that his knee was bobbing up and down. And I was thinking, 'Wow, if Jerry's nervous, this is a time maybe for Chris to get nervous also. Maybe this is actually going to happen today.' I think having a mix of rookies and experienced astronauts onboard a spaceship is a good idea.

James - So that was your first space flight. The second one you so viscerally described at the beginning, in 2001, where you did 2 spacewalks. Your final mission in 2012, that's the long duration one to the ISS where you are the commander, right? How does the preparation differ from the matter of days you spend up there for the first few missions to the matter of months for the final one?

Chris - My first two space flights were as part of the flight crew of American Space Shuttles and we were just like a visiting construction crew. We would fly in, we'd dock with, in the first case, the Mir Space station, and the second case, the fledgling International Space Station. We were the hard hat crew, showing up to build something for a week or so and then coming home again. That's a very specific, discrete, deep, complex series of tasks and so that's the pacing and the ethos of what you're doing. It's the difference between going to build something for the weekend and moving somewhere. It's a whole different mentality, and how you prepare for it and the depth and breadth of problems you might face. And we were moving internationally - I'm moving to a country where they speak a different language and it's all different technologies. I was moving there, this time, not in a space shuttle, but in a Soyuz. So first, I had to learn to speak Russian and then I had to learn orbital mechanics and control theory in Russian and then to fly a Soyuz spaceship, in all emergency cases, talking to the centre for flight control on the outskirts of Moscow so I can talk directly with everybody there no matter what emergency happens. It's a whole different type of preparation. And then I'm also going to be the commander of the world spaceship, so that level of responsibility for the lives onboard, I'm their commander - if something goes wrong, the real buck is going to stop with me. We're running 200 experiments on the space station, so you have to travel to Japan and train for months in Japan on their part of the space station and all of their experiments and meet with the scientists from all around the world. It's quite a demanding task because, once you get there, yes you can talk to Earth for them to help you, but whenever anything goes wrong, very often the very first symptom of something going wrong with a spaceship is you lose communication with Earth. If it's a power problem or an altitude control problem where the Space station starts tumbling or something, probably one of the first things you're going to lose is communication. So you have to be able to do everything autonomously. It's a bunch of work.

James - Speaking of communication with Earth, this is the point at which you shoot to internet fame, spreading descriptions of how you accomplish basic tasks in space, like brushing your teeth, for example. But also the Space Oddity David Bowie cover, which most people listening to this I expect will have seen. This is where your powers as a communicator start to be realised and, I suppose, you set in motion the career you've moved on to have afterwards?

Chris - I haven't changed. On my first spaceflight, I was on the cover of Time magazine, so it wasn't like it was unrecognised. But there was no internet then and there was no social media. Also, onboard the spaceship on my first space flight, how could you communicate? There was a Ham radio. It's very difficult to mass communicate with a Ham radio. And we didn't have digital photography, it was film. So I could take a great picture of a volcano erupting, but no one was going to see it for months. If I want to go somewhere and show it to someone, I can't just email it to them or put it on Twitter. I'm going to have to actually travel somewhere and project it on a high school wall. Part of the reason I could share the experience so much more effectively on my third spaceflight was that we had WiFi on the space station. We had slow and intermittent but fairly capable connection to the internet from the International Space Station, so now I could see something and take a beautiful picture of it and then just look at it and write a little comment and send it. It just took a matter of seconds and suddenly I could bring a billion people along with me. It harked back to when I was that little kid who was so inspired by the NASA programme and the people going to the moon and the way that NASA so brazenly shared everything that was happening. You're going to get real communications and if someone swears up on the spaceship on the Apollo ship, then so be it. And Buzz did swear! It was like, 'Oh well! We all know swear words. Too bad.' So I just thought, 'Wow. If that was so influential in my life because of their willingness to share the humanity of that experience, then I should do the same. We set records for the amount of science we got done. It wasn't just us, but the momentum that had built, the station was mature enough. So we were getting all the work done, and we had a big emergency where we had to do an emergency spacewalk to save the life of the space station. So we were doing all of the technical stuff, but I also tried to intersperse using the technology onboard to share it as best as I possibly could, including the guitar that is permanently on the space station that was put there by the NASA psychiatrists. I thought, 'Hey, I'm a guitar player. I'm going to write some music up here.' They give me time to sleep, I'm going to steal some of it to be artistically creative and just try and help as many people as possible get this as part of their thinking so that maybe it'll help them make different decisions with their lives.

James - They're brilliant videos if anyone hasn't yet seen them.

28:27 - Chris Hadfield: Are we on the brink of finding ET?

Chris Hadfield: Are we on the brink of finding ET?

Chris Hadfield

James - Speaking as a producer of science radio programmes, it feels like a really exciting time in astronomy and space science. The first thing I wanted to get your view on is the recent resurgence of interest in the Moon and getting back there. We had India's Chandrayaan launcher just recently, Russia and China have expressed interest, thoughts of a lunar base. What's the timeline on this sort of thing?

Chris - Well, I think the biggest driving discovery has been water on the moon. If the moon is an inhospitable desert, then you have to bring every single thing with you and it's no place you're going to want to live. But over the last decade, our sensors have found vast reserves of water trapped in the shaded parts of the moon, especially at the South and North Pole on the order of 400 billion litres. And so if you have power from the sun like we do at the poles, because the sun is always visible and you have vast reserves of water, then what you really have is Sunny Waterfront, and everybody wants to live at Sunny Waterfront! That's the real estate on Earth and that real estate is now being very much contested. China have said we are going to have Chinese astronauts walking on the moon by 2030.

Chris - And there's already a crew, including three Americans and a Canadian, who are assigned to go to the moon probably early in 2025 and all those missions after that. There are 77 national Space Agencies in the world, not just the UK Space Agency and NASA and whatever, but 77 countries. All of them realise this is a huge new continent of resources and opportunity. With our improved rocket technology, with SpaceX and such radically dropping costs, suddenly it's like we've gone from sails to steam. Suddenly, this is now way more possible than it was even a decade ago. I'm very much involved with that, with technology incubation, with the Open Lunar Foundation, which is looking at what laws should be and how to influence it. I'm working with King Charles on a project called the Astra Carta to look at how we can make all of our efforts think about the long term and the ethos of it and the sustainability of it. I'm very much involved in that.

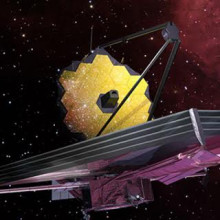

James - The other thing totally revolutionary for space science at the moment is of course the James Webb Space Telescope. One of the most exciting discoveries recently, from my perspective, has been K2-18 b, the exoplanet where we've found methane and the tentative suggestion of dimethyl sulphide: the so-called slam dunk chemical for life. The prospect of life elsewhere in the universe is really starting to grow.

Chris - For the last dozen or 15 years we've been able to detect planets around other stars. But what the James Webb Telescope gives us is a technical capability to see the atmospheres of those planets. With the stars behind them, you can look at how the light is changed as it comes through their atmosphere and look at the spectrum and see what's being absorbed and therefore find out that there is methane and other telltale life chemicals prevalent in the atmosphere and that's really tantalising. Are we alone or not? That little helicopter on Mars has flown over 60 times now, and the big rover is drilling down into Mars, looking for fossils, looking to see if life ever developed on Mars. We're going to send a probe to Europa, which has more water on it than Earth, and it's warm water. So there may be life on Europa and maybe James Webb will see something that is conclusive to show us definitively that we're not alone in the universe. As much as UFOs are fascinating and extraterrestrials make for great movies, we have never had any actual proof or evidence of life except from Earth so far. And maybe we're right at that moment in history where we're going to find out that there's life elsewhere.

James - And on that note, Chris Hadfield, thank you so much for your time.

Chris - Thanks James. Lovely to talk with you.

Comments

Add a comment