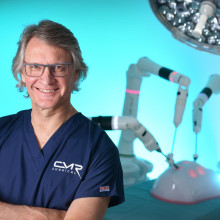

For this edition of Titans of Science, Chris Smith sits down with Mark Slack, a doctor revolutionising the use of robots in medicine. They discuss his early years in apartheid South Africa, how he established himself as a surgical innovator in the UK, and what the future holds for the use of technology in the operating theatre...

In this episode

00:59 - Mark Slack: Growing up in apartheid South Africa

Mark Slack: Growing up in apartheid South Africa

Mark Slack

Mark Slack was born in Johannesburg, South Africa. He grew up in a tiny mining community called Springs - which is near Johannesburg. Although many of his friends would attend private boarding schools, Mark went to his local state-run Springs Boys High School where he excelled academically.

Chris - Tell us about your life in South Africa and growing up there. It was an interesting time. What decade did your life begin in?

Mark - Well I was growing up in South Africa at probably one of the darkest moments of its history. Apartheid was in full swing, this was in the sixties, seventies and eighties. Because I was, I suppose, lucky enough to be born into a liberal, left-wing family, I had the negatives of it explained to me quite clearly from a young age.

Chris - In terms of academic prowess, academic performance, interest in science, are you from an academic family?

Mark - No, not at all. My father was in the mining community with no higher education. My mother was, again, not formally educated with higher education, but a very bright, intellectual person.

Chris - Presumably gold mining if you're outside Joburg?

Mark - Yes, very much gold mining. Those deep mines are not an understatement. I actually worked a holiday job at university on gold mines for a year or two, so had firsthand experience of it, yes.

Chris - Going down those shafts? They're five or six kilometres deep, some of them.

Mark - Yes. I think the deepest single drop is about one and a half kilometres, and then you get in a train and go to another one and you drop again. But I worked as a medical student in my holidays controlling the lifts that went up and down. You'd go up and down in them, they were dark, wet, cold, but some very interesting and funny experiences in doing it.

Chris - Sounds like some of the hospitals I've worked in.

Mark - Exactly!

Chris - But where did the interest in science stem from?

Mark - I suppose that's a sort of a personal journey as well. My primary ambition when I was at school was to run round a track two times faster than anybody else. I was a middle distance runner and that was my consuming ambition. Towards the end of school, I started getting injuries and then was shoved off to see a range of doctors because, as you probably know, in South Africa, sport is a religion. It's not a sport. When this young champion was no longer doing as well as he should have, I was sent to the great and good of medicine. It turned out that I had an underlying medical condition that contributed to the injuries.

Chris - But was that what inspired you then to become interested? Was it the science or was it the human side or was it both that made you think, well, maybe this is a career for me?

Mark - It's a combination. 1) I suddenly got exposed to all these people doing something that I thought, 'Gosh, that's interesting.' 2) I admired the people that were looking after me and fixing me. Around about the same time the teachers started saying to me, 'Now, you do quite well at school, you're quite bright. Why don't you do medicine?' And so the combination of the three sort of amalgamated.

Chris - You went to Wits University to do that. What was medical training like in South Africa? It's an interesting country because it has huge prominence, surgically - Christiaan Barnard being probably the best known, famous South African surgeon.

Mark - The training was incredible. We were so spoiled. I always say this with a tinge of remorse as well because my class was virtually 90% white, and so we were benefiting from the legacy of apartheid. The kids in my class were academically all totally capable - they all had straight A's - but we had a very well-funded education system.

Chris - It's changed now, though, hasn't it? Things have flipped around in some respects. I was in South Africa recently. I met a young woman, white woman, who was at the top of her class, but she couldn't get into medical school because there were not enough places for white people now.

Mark - Yes I think there has been a positive discrimination act, which I find very difficult to criticise given the decades where exactly the opposite happened to the black South Africans. And I think for South Africa to succeed, there has to be a degree of positive discrimination in favour of black South Africans. So I see the difficulty it creates for the individuals, and I feel very sorry for them, but I also see the need of the country to promote people who've been disadvantaged and their parents wouldn't have had the same education, etc. So I find that difficult to be critical of.

Chris - You don't think there's a danger of it going too far and the country will lose some of its skill, some of its finance, I suppose, because people will be pushed out and they'll take their skills and their money with them?

Mark - In some ways, they'll take a little bit of hope from the recent rugby World Cup. When South Africa got rid of apartheid, there used to be a facetious term talking of rugby players, the black Springboks, they would call them 'quotas' because there was a quota of having X number of black people in the team. And South Africa, as you know, has recently just won the World Cup with a team with a high number of black players who are 100% there on merit. I hope that the meritocracy will come back, that you need it for a while to right things but, thereafter, there are more than enough highly intelligent, talented black Africans who are capable of shining. It's a terrible loss to South Africa of some of its real talent and that's, unfortunately, for the low and middle income countries, an international problem.

07:26 - Mark Slack: Moving to the UK

Mark Slack: Moving to the UK

Mark Slack

Chris - You go through medical school. Where does military service fit into your career? Is that done before, during, or after medical school?

Mark - So when I was at school, military service was supposed to be done at the end of school. It was one year and we could get permission to defer that to go to university, which I did in the hope that military service would have disappeared by the time I got to the end of medical school. But, by the end of medical school, military service was two years - so that was an absolutely spectacular own goal. However, you had three choices; you did your military service, or you went to jail, or you left the country but there was no return. I didn't have the moral fortitude to go to jail for seven years, so I elected to do my military service as a doctor serving in the army.

Chris - I spoke to a South African who was in the armed service and he said that military service was really quite fearsome in South Africa. He described an experience that they called the 'Garden of Pain.' Are you familiar?

Mark - I'm not familiar with that particular term, but it was quite fearsome and training was fairly fierce as well. It was an interesting one. I volunteered to serve a lot of my time in my national service in Angola because that way I wouldn't be serving against South Africa... There are lots of moral and ethical discussions about it, and one or two of my friends actually chose the other way and went to jail, for which I admire them terribly. But it's a difficult decision to make.

Chris - What was the gig in Angola, then? For people not familiar with the geography of Africa, that's a bit further up the continent. So what was the relationship there and why was there a presence in Angola?

Mark - It's a complex one. South Africa had Namibia as a protectorate. It was a legacy after the Second World War. They controlled it and they wanted to keep controlling it. Angola was under Portuguese control and the Portuguese suddenly left almost overnight. At one point there was a war of independence going on. There were three rebel armies fighting the Portuguese, and one was Marxist based, unsupported, and the other two were American based. The Portuguese suddenly said, "Oh, enough's enough. We're out of here" and they left, literally. So then there started a civil war with people supported in the North by Russia and Cuba and the armies in the South supported by America and South Africa. South Africa wanted to do it to keep the freedom fighters for Namibia further away from the border, but it was a South Africa supporting Angolan civil war with Angolans fighting Angolans.

Chris - So you did that for two years and then you came back. Was that when you travelled down south and went to UCT, University of Cape Town?

Mark - The army, ironically, was the reason I landed up in gynaecology as well. We would fly out of Northern Namibia, pick up the people, bring them back, they'd be operated on, and then we'd fly them home. I did some time working for one of the rebel armies as well, as a medical officer. But when you were on what they called 'R and R,' 'Arrest and Relief,' I was then put in the military hospital in Pretoria and I was placed in the gynaecology department. There was a really inspirational man there called Dick (?), who's the head of the gynae department. He said "Oh, what are you going to do in the future?" I said, “I'm going to be a physician. That's my academic bend." And he said, "You probably can't pass the gynae exams." Cut a long story short, he persuaded me that this could be a really inspiring career and I still had to think about it when I came out. I went back to thinking about doing internal medicine, but he'd planted that seed. Then I moved down to Cape Town to do gynaecology formally as training.

Chris - How long were you down there for?

Mark - I was in Cape Town for about six years. It was a combination of obstetrics and gynaecology. I worked at the famous Groote Schur hospital where the world's first heart transplant was. In fact, I can remember one day operating, doing a very minor procedure, and then becoming aware of a plaque on the wall that said, 'This is the theatre where the world's first heart transplant was done.' I'm pleased to say they've now converted it into a museum and it's no longer being used by low level gynaecology trainees.

Chris - I've driven past that building just recently, in fact. I was in Cape Town quite recently and it's a very impressive building, isn't it? You drive past on the motorway from the airport going into Cape Town.

Mark - Yeah, it's a beautiful building, the old Groote Schur. Of course, the main hospital's now in the modern building in the front of it and that's largely medical school and so on. But that's the hospital I trained and worked in. The style of delivering care in Cape Town was quite unique. It's something that I think the world could learn from: they didn't have enough doctors, so they promoted using what we called 'midwife units' to deliver a lot of the babies who had strict protocols. When you got problems, where there were problems, they would be transferred across to the main hospital. So they actually delivered a high level of care in delivering babies in a much more affordable way, and without the same numbers that you would've had in Europe or UK in terms of obstetricians, gynaecologists.

Chris - Many people who come to the UK from other countries, though, pregnant women who are going have a baby, are quite surprised that we have midwife led birthing units here. They're quite used to a very medicalised way of having children in their own countries, America especially.

Mark - It's a very difficult and controversial area. I don't think one size fits all. I think the two professions need to work closely together and, in fact, they have got that far more. I think the argument, "Everything's got to be a natural delivery" - multiple reasons why that's nonsense. And "Everything's got to be a medicalised delivery" is equally not a good one. I think the hybrid model that Cape Town actually had, working with respect for each other and for the constraints and the limitations was, actually, in retrospect, an amazing system.

Chris - When did you first come to the UK?

Mark - We all used to come to the UK to do a bit of extra training - I won't repeat the term that was used, but anyway. It was coming to practice, our surgery, and the NHS was seen as a fantastic place to practise; high levels of care, high volumes of work, low numbers of doctors. The waiting list is almost like an Argos catalogue: "I'll have two of those, three of those" and we all came to district hospitals. So I trained in a teaching hospital in Cape Town and, in fact, my whole career was in teaching hospitals, but I then actually came to work in a DGH in Canterbury in the United Kingdom. That was my first job and it was just an incredible experience. We saw so much and we are allowed to do a lot. It was a great early experience - I just forgot to go home.

Chris - So that was literally the first and last time you came to the UK to do medicine or surgery?

Mark - I'd been given a senior lecturer post in Cape Town and I was just coming for a year or two. And after my first year I asked for an extension, which I got from Professor Davey, and then, after my second year, when I said, "Could I have a third year as extension," he said, "You make up your mind now - you either come home and your job is here or you stay there and your job is gone." And I stayed.

Chris - When are we talking? Mid nineties?

Mark - This was in the late eighties, early nineties. And I'll be quite honest, one of my reasons for staying was I really did not believe that the South African government was going to capitulate and give up apartheid. A lot of us were looking for a way out of a system that we felt was just destroying a country, destroying people, and so a lot of my generation left.

15:08 - Mark Slack: Innovating new medical technologies

Mark Slack: Innovating new medical technologies

Mark Slack

Chris - How did you then end up on this path to where we are sitting today? You've come to the UK, you are working in obs and gynae and you're doing academic/clinical work around that. But how does that translate into being a co-founder of what's dubbed in the industry a 'unicorn,' a business that's gone from a startup to worth more than a billion in valuation in a very short space of time? Take us on that journey.

Mark - Going back, Chris, to your original question, you said to me, "Why medicine?" There was the personal, meeting the doctors, there was the fact that my teachers were saying, "Well, you do quite well at school so maybe medicine is a good line for you," to getting into medicine and finding, gosh, I really enjoy this, this is really fascinating and there was just so much that I found interesting. And then, when I qualified, it became even better. I really found I enjoyed it. I became quite obsessed with it. When I first came to the UK I was now a qualified gynaecologist and working in a DGH, but myself and an Australian colleague started introducing new operations which hadn't been done in the UK before, which we introduced and wrote up and published. I met this chap, Marcus Carey, who's the professor in Melbourne, and I met him in Canterbury. We've now had a lifelong of working together academically and that was the spark of what really became my expertise. I realised I think quite laterally - I would have ideas and one of my professors took me aside one day and he said, "You know, Mark, you've got some really interesting ideas in your head. Just keep them in your head until you have the proof to justify them." That was the best advice I ever got because I then started learning to do the research to prove the points that I was trying to convey to people.

Chris - And how does that turn into the technology that you've gone on to help develop?

Mark - So the first one we introduced was an operation called Sacrospinous Fixation, which was the first paper of its kind in the UK and it's a very commonly performed procedure now. I was then doing a lot of research and doing a lot of pharmaceutical trials, and that's when I started finding that I would see things and think, 'That doesn't make sense and perhaps it could be done differently.' So I co-invented a machine to measure pressures in the bladder and so on, which was then taken to global launch by Johnson and Johnson. Then I did another operation with Marcus which, again, we took to global launch with J&J. So it grows. You start and then, I suddenly realise, 'Well, I have a skill here where I seem to have ideas that I can translate to something relatively useful.' That is the next part of that journey ahead of the robotics starting.

Chris - How did the robotics get started, though? Was that because, all of a sudden, there was a technological revolution? The internet's there, so there's rapid transmission of information and data, there's computers that are sufficiently powerful to make this sort of thing possible, there's cameras and endoscopes and that kind of thing that make this kind of technology now possible. Is that how it happened?

Mark - There's a far more simple story as well. One of the things that's happening is, I trained a lot of laparoscopic surgeons and realised that I couldn't train all of them to do the operation at a level that it really needed to be done at because laparoscopic keyhole surgery, as we should rather call it for the listeners, is technically really difficult and not everybody can master the technique. I was worrying, what can we do? And then of course, as you say, there was all this technological advance; there was a robot out on the market, there was computer driven early AI starting to help in all these areas and I started to think, could a robot, which has got 3D vision instead of 2D vision, it's got magnification, if you move your arm right, the instrument goes right whereas in keyhole surgery you move your arm right, the instrument goes left - there were lots of things that I thought, 'Gosh, that'll make it easier to do.' I was then looking at the robots that were around and trying to work out whether this would be a solution. But that's not actually how I got into robots.

Chris - And how did you get into robots then?

Mark - So my wife was pregnant with our first son and she was attending the National Childbirth Trust on her own and, after a couple of weeks, the woman in charge said, "Do you have a partner?" And she said, "No, I'm married." And she said, "Well, you must bring him along." And my wife said, "Believe me, leave him at home." Far less disruptive. Anyway, Luke, my co-founder then came to my wife and said, "I believe you're a surgeon." And she said, "Yes I am." And he said, "I want to speak to you about robotics." And she said, "You're speaking to the wrong member of the family. The other one at home is going on about it as well." And so Luke and I, both of us having careers where we've done lots of innovation, lots of inventing, met by chance. And it's one of those - God, I'd be presumptuous to say - but it's almost like a Beatles moment where you meet somebody special who compliments some of your own skills and talents. Luke was just inspiring to meet: intelligent beyond belief, competent, and he came round to my house, as I always say, in a car that shouldn't have been on the road. We sat down and started to discuss it in my drawing room on the ground, drinking Diet Coke. And that's literally where it started.

Chris - Imagine if you'd been drinking whiskey, it might have gone even better!

Mark - Or faster! Exactly. So Luke and I, he would then come around every evening. He worked not far from where I lived and he'd come around and we'd discuss things. I had very clear ideas of what I thought was important. He had very clear ideas and then, of course, the other founders were there as well, Paul and Keith and Martin. It literally started with five of us in Cambridge, all people working in and around Cambridge, most Cambridge graduates but all working in the ecosystem.

Chris - So what was the gap you spotted where you thought, this is the existing solution, this is the problem, this is what we can solve, and what did you do about it?

Mark - Well, the big gap was, keyhole surgery's been around for 35 years so, if it was perfect, about 80% of surgery by now would be done by keyhole, but only about 40% is. Now, keyhole surgery has a million advantages over open surgery: it reduces infections, it reduces pain, it reduces complications. And yet, despite all these advantages, in America, 'the most advanced medical system in the world,' only 40% of surgeries are done by keyhole. So clearly there's something wrong with keyhole surgery - and it's technically bloody difficult to do, beyond the reach of some people. So, could the direct mapping, the 3D vision, the precision of the instruments, etc., overcome that? That's what we set out to do. The robot that Luke designed was an open console allowing good communication with the teams, the hand controls just made life so much easier. I taught one of the secretaries of state to tie a knot in about 30 minutes. If you were dealing with normal keyhole, that would take about 60 hours.

22:42 - Mark Slack: CMR Surgical and beyond

Mark Slack: CMR Surgical and beyond

Mark Slack

Chris - Set the scene, then. A person who sits down at your robot, what's their experience as a surgeon compared to if they've got to stand over the patient with the probes going in to do keyhole manipulations. For people who haven't seen this, you blow up someone's tummy with gas and then stick tubes down that you then put your tools in, don't you? So how does this differ when they're using your robotic experience?

Mark - The big way that I show this to people who are not necessarily keyhole surgeons and so on, is I use what we call a dome; so, it's a model and I hang a tiny needle on the end of string, into the dome, and I give them a normal laparoscopic kit and say, "Pick up the needle." And they can't. Then, I do the same in a robot: I put the needle into a dome, I put the robot into it and I say, "Try and pick up the needle." And, instinctively, they can get across and pick up the needle. So I believe we can train people much quicker and much more effectively on a robot than we can with keyhole surgery.

Chris - Is the robot intervening in the procedure? When you move, presumably a joystick or a paddle, to manipulate the objects inside the patient, is that a direct connection or is the robot saying, I know what Mark wants to do, but he's not doing it as well as he could so I'm going to intervene and change it a little bit to make it even better?

Mark - Not yet. That's, I think, quite a while away. At the moment it's a slave master. The surgeon remains the master and the robot is a slave. What it does is it gives you better vision, it gives you precision, it gives you better control and, as I said, it reduces training duration. But at the moment it's still 100% - all the decisions, all the work, all the movements - are controlled by the surgeon that's operating it.

Chris - Could you, in the future, do that, though? Could you see a future where you, as an expert in some of those procedures that you've helped to pioneer, could sit in Cambridge and operate on somebody in Cape Town?

Mark - Telesurgery is a big and interesting area. Some years ago, they did an experiment where a surgeon called Jacques Marescaux operated in Strasbourg on a patient in New York. But in order to achieve that, they laid a cable, and they did it the day before 9/11 - so they got not a lot of publicity out of it. There's trouble with the speed of light. If you are operating a very long distance away, when you move your hand, the instrument will be slow to move on the screen behind you. Technologically, we will overcome those things to a degree. At the moment, what we do have is, when we did our first lung case in Germany, the surgeon supervising - it was the middle of Covid, it was in England - was able to watch over a television monitor and give advice. That's something that's growing quite fast. Actually having a surgeon operate remotely, it's a whole different conversation because would you want your surgeon to be 300 kilometres away when things went wrong? I don't know.

Chris - What about doing a road test on a procedure? Everyone's different, everyone's anatomy is different inside so, therefore, though we have a generic way of approaching things, it's the skill of the surgeon being able to drive over those bumps in the road that are going to be specific for that patient. So can you take your system, take really high quality scans of that person, build a sort of rendition, a mock up, and almost play a computer game to try out your approaches to see what's going to be the best way down that road? Is that one way to learn or to try tough procedures?

Mark - Now Chris you've got me worried that you've been going through the company's files! I think that's one of the most exciting areas. I've just been visiting a simulation laboratory where they make really high fidelity models. And so, yes, I do see you could do a scan of a person's anatomy, you could build the model out of plastic or synthetic substances, and the surgeon could then practise the surgery ahead of going in. I do think that's within reach, very soon in fact.

Chris - Did you think this was going to take off the way that it did? Did you see yourself sitting here, we are in one of your offices, that's a sign of success, isn't it, that you haven't just got one office in one building, you've got multiple buildings in multiple places. Did you see it taking this trajectory and at this sort of pace and reaching this sort of scale when you started all this?

Mark - No, not at all. As I always say, if I knew then what I know now, I probably wouldn't have started. But anyway, here we are. I thought it'd be like all my other projects that I'd brought in. I suspected I'd continue to be a gynaecologist at Addenbrooke's practising happily and then I would do a day or two a week at the robot. But it just became impossible. I couldn't keep up. While I've maintained a very close contact with my colleagues in Addenbrooke's, and I have an honorary contract, I had to come full time because the volume of work was so high. Did I see it going where it's going? I hoped it would. What people don't realise, Chris, is that thousands of people, millions of people, are injured and die as a result of poor surgery, and something's got to be done internationally to improve surgical training and surgical outcomes. I think the robot is one of the ways of achieving that goal. A million people die in the world due to surgical complications. That's a big figure. We give the coronavirus a good run for its money.

Chris - How do you switch off at the end of this? Is it sports, still? I know when you were younger you said it began really running around a racetrack, that brought you into contact with the medical profession. Are you still doing that kind of thing? You still derive that pleasure and that switch off opportunity from sport? Or do you put your energies elsewhere?

Mark - People said, do I still run? I said, "I think these days you'd call it jogging." So I don't run competitively at all. I still like to go out and do a bit of exercise. I love sailing. My wife introduced me to dinghy sailing, so it's nothing big or expensive and we like as a family to sail and my boys sail as well and that's lovely. I also have two daughters. They don't sail, but I'm ambitious I can persuade them to join us. So sailing for me is one of the places I get away completely, I walk away from everything and I get in the water and I'm pretty bad at it. I'm sort of sailing for my life as such. The other one is I enjoy cooking and I don't know that I'm a stunning cook, but it's again somewhere where I can switch off a bit and just enjoy it. I just enjoy time with the family, going for walks and things like that. I don't switch off as well as I should - my wife does have a complaint about that.

Related Content

- Previous Are some wildfires beneficial?

- Next Does Mercury have a moon?

Comments

Add a comment