Stem cells made by reprogramming a patients own cells have the potential to revolutionise personalised medicine. But are they safe?

A paper in Nature this week urges caution after finding that current techniques involving the addition of up to four genes to "reprogramme" adult cells so that they revert to a stem cell state can also leave the cells harbouring potentially harmful mutations, some capable of causing cancer.

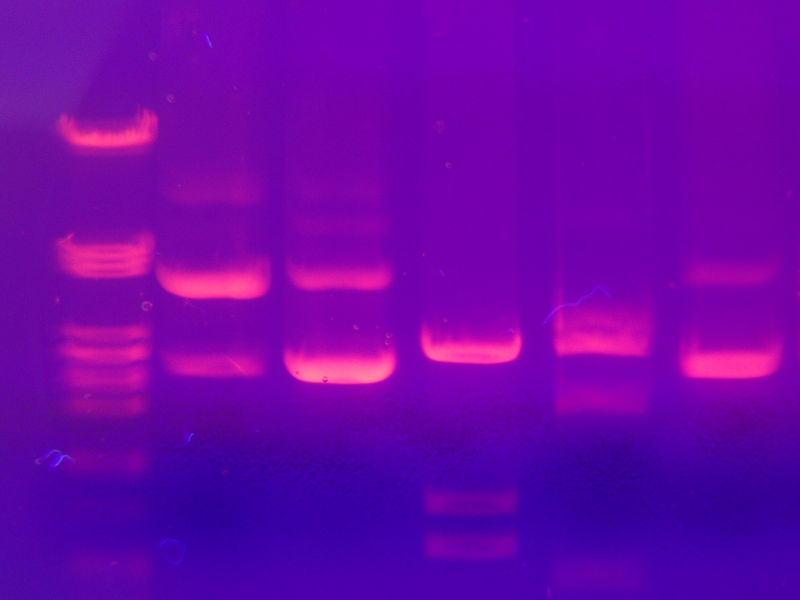

Study author Kun Zhang and his colleagues genetically sequenced 22 lines of so-called iPS cells - induced pluripotential stem cells - produced by seven different laboratories using several different techniques. They then compared the resulting genetic profiles with the corresponding sequences of the parent cells from which the stem cells had been made. They were surprised to find tenfold more mutations (DNA changes) in the stem cells than would be expected normally for cells kept in culture, and these changes appeared to be permanent, remaining present when the cells were grown for over 40 generations.

Study author Kun Zhang and his colleagues genetically sequenced 22 lines of so-called iPS cells - induced pluripotential stem cells - produced by seven different laboratories using several different techniques. They then compared the resulting genetic profiles with the corresponding sequences of the parent cells from which the stem cells had been made. They were surprised to find tenfold more mutations (DNA changes) in the stem cells than would be expected normally for cells kept in culture, and these changes appeared to be permanent, remaining present when the cells were grown for over 40 generations.

They were also not a random smattering of changes but instead were more than twice as likely to be "missense" mutations that would directly alter the structure of the protein encoded by the affected gene rather than silent "synonymous" changes that don't actually alter protein structure.

This indicates that strong selection is at play when the cells are being produced and that those that tend to grow best might be the ones that have more of these sorts of changes.

The researchers aren't sure yet what renders the cells more vulnerable to mutation during the reprogramming process, or when the changes occur.

"These studies look at two different aspects of stem cell mutations," says Zhang, "but their take-home message is the same - things can go wrong at the genome level when reprogramming and growing reprogrammed cells. So, to maximise safety, before we put these cells back in the human body for therapeutic purposes, we must be sure that the cells contain the same genome as the recipient, with no cancer-causing or other serious types of mutations."

Comments

Add a comment