COVID retrospective, space security, and car brake particles

In the news pod, 4 years on from the outset of the COVID pandemic, what questions still need answering in the bid to avoid a similar emergency? Plus, why we need to start taking space security more seriously, how car brakes could be more polluting than exhaust fumes, and Paul Alexander - who lived inside an iron lung for 70 years - dies at the age of 78.

In this episode

The COVID pandemic: 4 years on

Maria Van Kerkhove, World Health Organisation

It has been four years since the World Health Organization first declared COVID-19 a pandemic. The ensuing outbreak, which left millions dead, was the worst in more than a century. It also severely hampered the education of children and students worldwide, and strict lockdowns battered the global economy. I asked one of the key players at the World Health Organisation for her recollections of the situation 4 years ago, and the questions we still need answers to today about where the virus came from…

Maria - My name is Maria Van Kerkhove, I work for the World Health Organization. I'm the interim director of the Department of Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness and Prevention and, during the COVID-19 pandemic, I am also our health operations and technical lead. This week, four years ago, we reached the point where WHO characterised the global situation as being in a pandemic. It's significant in many ways because it's where the world woke up to the threat of Covid. The anniversary actually should have been the 30th of January, 2020 when we declared Covid - it wasn't even called Covid at the time - a public health emergency of international concern. And that date in 2020 should have been the time where the entire world and governments activated their systems to tackle this unknown threat so that we could have potentially prevented a pandemic.

Chris - Was the threat recognised and realised by people at that point? Did they know and were just hoping it would stay a Chinese problem? Or was there an element of, well, no one's done anything yet, so we'll just go business as usual until they do?

Maria - I think that's a good question. I think the perception of what the threat was varied around the world. There were certain governments that knew the threat immediately, and that was because of the muscle memory they had because of other pathogens like SARS, like MERS, like avian influenza. They knew that they needed to activate systems to mitigate that potential introduction of the virus and, if it did get into their country, what they could do to buy themselves some time so that their health systems didn't get overwhelmed. I do think that much of the world did not take this seriously despite warnings because they thought this is a problem somewhere else in the world, you know? Whereas six weeks prior where we were saying; it could become a pandemic, this could be something really bad, it is an emergency at a global level, activate your systems, prepare, prepare, I don't think many governments around the world really understood that threat

Chris - Because initially the World Health Organization reassured us that there didn't seem to be any evidence this was spreading among people. Now, is that just because you were going on what you were told by China at the time? Or were there questions: we don't know that this is actually spreading?

Maria - There were so many questions that we didn't know. Of course early on, what was reported from China, certainly they were adamant that there wasn't any human to human transmission. But even before that, the first press conference that I ever did was January 14th, 2020, where I was talking about - I think there were 41 confirmed cases at the time - that there was likely some human to human transmission among families. But for us, we had already issued guidance about preventing human to human spread. I had articulated the hallmarks of what Coronaviruses were because we have experience with SARS coronavirus, with MERS Coronavirus, and the hallmarks of these types of pathogens. This viral family are super spreading events. We did have some warnings out there, certainly there were mixed messages from China. We were very frustrated with this. We've been extremely vocal about this over time. Nothing I'm saying right now is new. Regardless of what was being released from China, there were a lot of questions about transmission: how was it transmitted? Who is most affected? How do we stop it? One of the biggest, biggest, biggest questions we had in the beginning was around household attack rates. What was happening within the families themselves? That was important to understand how transmissible this was. But there was so much uncertainty in the beginning.

Chris - You actually went to China, didn't you, in February, 2020. Were they cooperative and supportive of your endeavours, Maria, because you were one of, and have been one of the few people who have stood up and vocally not let them off the hook when you think that they have not done the right thing. So back then, even in February 2020, were they supportive or were they trying to obfuscate

Maria - When we were there in February 2020, I'm not talking about the first few weeks of the pandemic - and yes I have been very vocal about calling out China and other countries for that matter when they don't release the information - a lot of that relates to the origins of COVID 19. You and I have spoken about that before. But when we were there on mission, I remember sitting with colleagues and being very impressed at the level of data that was available at subnational level. I remember speaking to our counterparts at China CDC and saying, why aren't you releasing this information? Why aren't you making these sitreps available? In my experience with everywhere we went, and of course we didn't go everywhere, and I'm sure that the places that we went were selected on purpose, but we got answers and we pushed for those answers. Our focus was not on origins on that particular mission, though we did discuss it a little bit. Our focus was really on understanding what was happening, what this virus was doing, the disease it was causing, and what could be done and how do we inform the rest of the world. At that time, the most heavily affected country was China.

Chris - On that latter point, you mentioned origins, and it's not a question that's gone away: we still don't have satisfactory answers. The WHO has asked questions of China about this, and they haven't been very forthcoming, have they? How are you working towards trying to get us closer towards understanding why this happened, without finger pointing, but why this happened and therefore how we can prevent it again.

Maria - I think that's the point. It's not about finger pointing. It's really trying to understand. The origin of COVID-19 is still open. The only ability we have is to assess available information, and the key here is available information. We've asked multiple questions. Not just questions, there are recommendations of studies that need to be done, there are assessments that we want to have happen, in interviews to happen with labs that were in the areas in Wuhan where the first cases were identified. We don't have the answers to this. Despite repeated requests on this, we don't have the results of studies that follow or that trace those animals that were sold at the Huanan seafood market back to their source farms. We don't have that information. Most of the available information does suggest that we do have a zoonotic origin, that the market played a very important amplification role, but the market is not the origin of Covid.

Maria - The market is potentially where susceptible animals were sold, where people were infected. But the question for us is, where do those animals come from? And then, of course, we have to look at the whole spectrum of the potential hypotheses of what might have happened. One of those is looking at a breach in biosafety, biosecurity. We still can't answer that question because we still have not had the audits and the interviews with the labs despite repeated requests. So we're working with SAGO, our advisory group, to try to advance this. But the only thing that they're able to do is evaluate and provide an independent evaluation away from politics, away from any of these conspiracy type discussions, but really rooted in science. But you can only evaluate data, and I think the last time we spoke there was the release of information and data from 2020 from the market which infuriated me. There's even been a recent study that has just come out that has looked at a number of sequences from human patients, I think from January through September 2020. There's more data that exists that has not been released, and that's the frustration that I have, that the global community has, because we can't put this to rest. It's not just a scientific question, it's a moral question. It's about preparedness for the future. We need to know specifically what happened so that our interventions, our prevention methods could be much more precise.

09:22 - Security threats from space are closer than you think

Security threats from space are closer than you think

David Whitehouse

The former head of the NATO military alliance, Anders Fogh Rasmussen has said that politicians should not ignore security threats in space. Mr Rasmussen - who also served as the Danish leader between 2001 and 2009 - wrote in Politico recently that the “military threat in space is real, and it is growing” and that Western policymakers need to react. Joining me to talk about these comments is space scientist, author and former BBC science editor Dr David Whitehouse…

David - I think the Ukraine conflict has brought into focus a lot of the feelings and worries about space-based warfare that have been around for a long time. It is said in space warfare history that the Persian Gulf War of 1991 was the first space war in which space assets were a real importance to finding out what was going on on the ground and directing conflict. Ukraine is the first two-sided space war in the sense that Ukraine is not a space power, and yet it's been able to use space resources to aid its fighting in a much more efficient way than Russia has. I mean, Ukraine has used communications and it has used commercial satellite observations to find out what's on the battlefield. Russia, you would've thought, would have a space advantage, but it hasn't because it's outdated and it's not been able to get its systems to work. So for future conflicts, and people are talking in this respect, not about Russia, but about America and China, there are a lot of lessons to be learnt about the importance of protecting space, the infrastructure of space, during a conflict.

Chris - What sorts of legislation treaties, pre existing agreements are there to safeguard space, if any?

David - There are two that come to mind. The first thing that Russia did when it invaded Ukraine was hack the Viasat satellite system to disable Ukraine's communications. Ukraine responded by using a different set of communication satellites, the SpaceX satellites launched by Elon Musk. Legally, that actually means in terms of international law, that SpaceX is a participant in the fighting in the Ukraine. Under international law, Russia would have the right to attack a third party, which is aiding its adversary. That worries people a lot. But also the recent announcement by Russia that it was thinking about some form of nuclear powered weapon in space did force people to think again about the outer space treaty, which was signed in 1967, which prohibits the use of nuclear weapons or the kinds of weapons of mass destruction in space. And people realise that actually that wording in 1967 is rather loose, and that there are ways that Russia could put a nuclear powered weapon in space by not violating that treaty.

Chris - The other thing, of course, is that space is becoming quite crowded and there are predicted to be more than a hundred thousand satellites in space within the next decade. As some people have pointed out, you don't actually even have to put a weapon in space to weaponise space because all you'd have to do is to knock a couple of those satellites off kilter and there'd be potentially a runaway collision effect where everything would smash into everything else. You could cause a catastrophe and a major problem for everyone on the Earth's surface because of our reliance on space without actually having to fire anything anywhere

David - You are quite right. We are all vulnerable. There is a worry in the future that, particularly if a nation like Russia would get desperate, it could sabotage the whole space ecosystem for everybody. Because as you said, if you blew something up in space, you could create a self-sustaining cloud of debris which might achieve your military objectives, but it would blind you. It would blind everybody else. It would interfere with communications, with positioning television, with not just the military, but the whole space infrastructure. Satellite navigation in our cars might be affected by this. That would be a brute force, last resort strategy that military space planners don't rule out in extreme circumstances. As you imply, there is a whole space ecology on which society relies which needs to be not only investigated in terms of how vulnerable it is and how it could be attacked in space, but needs to be updated. It's very interesting to see the United States Space Force which is charged with protecting the American space system and developing ways to attack the Chinese space system in the future. They've been disappointed by the fact that they've got slightly less budget this year because they're going to spend a lot of money on upgrading, updating, and modernising all their space systems so that they could be more immune against attack. But you're right, if somebody blows something up and scatters shards of debris everywhere, there's no protection against that. So people need to talk.

Car brake wear particles are charged and cause inflammation

Jim Smith, University of California, Irvine

Much of the discussion on the role that car emissions play in climate change centres on the emissions that come out of the exhaust pipe. But researchers in the United States say we should also be paying closer attention to the particles that our cars emit when we brake. It turns out that these brake wear particles, which can be just as small as some exhaust particles and trigger inflammatory reactions in the body, actually carry an electric charge; this is both a blessing - because it makes them easy to remove, and a curse, because that can keep them airborne for longer. Jim Smith is from the chemistry department at the University of California, Irvine.

Jim - This is a project that actually has roots back in 2016 to the Volkswagen emissions scandal. As a result of that, Volkswagen gave the state of California a sum of money for research on vehicle emissions and so we applied and we were awarded a two year grant, landed into this area of measuring the properties of brake particles: particles that come from not the tailpipe, but from other sources such as brakes and tires, from road surface wear. They've actually caught up to the emissions that are coming from tailpipes. This is an area of growing concern. We really have no regulations on how cars may or may not be able to emit particles from other sources besides the tailpipe.

Chris - And I suppose as we transition more towards vehicles powered electrically, the proportion of pollution that comes from these other sources like tires and brake pads is going to increase.

Jim - Absolutely, yeah. We love electric vehicles for the impact on our greenhouse gases in the environment, but if you think about it, electric vehicles are not truly zero emission vehicles. You'll always have these other sources unless you have ways of controlling the emissions from these sources.

Chris - And how big are the particles, Jim? Are they on par with what we're worried about with very small particles coming from exhaust pipes, or are they in a totally different regime entirely?

Jim - Actually, surprisingly, they can be quite small. This is something that surprised me a lot. Before I started research, I thought, well, most of these must be large bits of brake material that go into the air. But you can actually create very small particles that can actually penetrate deep into the human lung and actually cause a host of different health ailments. We should really think of these non exhaust emissions as being quite comparable to exhaust emissions in the actual size regime of the particles being produced.

Chris - So what did you actually measure, and what did you find when you were looking into this?

Jim - We went into our machinist workshop and we asked the the machine shop if they could let us use one of their large metal working lathes as a way of spinning the disc of a brake, built a chamber around this lathe, and we were able to replicate the action of braking. We brought all of our equipment in and we started making measurements mostly of the physical and chemical properties of brakes. At that point, it didn't really occur to us to think about the charge or whether or not particles themselves might have anything other than just chemical properties and a different size regime.

Chris - Well you've piqued my interest now. What's special about the charge, then?

Jim - Well, actually, the idea came from one of my colleagues who said, when you rub things together, you actually can create charge on surfaces. He said, well, braking is exactly that: it's rubbing two surfaces together. I wonder if particles produced by brakes could have a charge on them. I thought about that and I said, that makes a lot of sense; let's go try that out. We immediately were able to measure charged particles that were produced from this braking process. It's a very similar mechanism to what would happen with a balloon. If you just rub a balloon on a sweater or your hair like I used to do when I was a kid, and then stick it to the wall, I used to marvel at that. That was such an interesting phenomenon. What you're doing is you're transferring electrons or charges from one surface to another, and essentially that's what is happening with these particles. The act of braking generates this mechanism by which charges get transferred to these particles, and you can think of these particles as little balloons that just got rubbed on a sweater and are now floating in the air with all this static electricity on them.

Chris - And why does that matter, the fact that the particles have a charge?

Jim - Well, there's a couple of things that I think are really interesting about this. For one thing, when you take some of these particles and put them in liquid, they'll actually create a kind of oxidant that actually can be harmful to health. And so if they're charged, this provides us an avenue from which we can actually remove them from the source itself.

Chris - A sort of scavenging system? So as the car is making the particles, rather than them being released into the air or the road surface, you try and grab them before they get away?

Jim - Yeah. So the fact that they're charged means that we can apply an electric field that will provide a force on those charged particles and allow us to sweep them away before they even have a chance to exit the braking system. Our research has shown that up to 80% of the particles coming off of brakes could have a charge on them, so you could immediately remove about 80% of the particles coming from this important source of pollution using electric fields.

Chris - We've predictably dwelled quite heavily on the human health implications, but are there any environmental impacts as well of particles? Can you foresee any role for these sorts of charged particles when they go beyond where they might hurt us directly and be doing things environmentally?

Jim - An insight into this actually comes from research that's being done on dust particles in the atmosphere. It turns out there's been a big mystery in the field of atmospheric science which is, how is it that relatively large bits of dust that come, say, from the Sahara Desert can actually stay in the air for weeks at a time? It turns out these particles, in much of the same way that these brake particles are acquiring charge, actually acquire a little bit of charge in the process of being swept off of the desert. A lot of people know that the Earth has a magnetic field. Well, it turns out the Earth actually has a very weak electric field as well. Even though the earth itself is neutral in charge, the surface of the earth has a very slight negative charge. And the base of a cloud, say, for example, in the atmosphere, will have a very slight positive charge. It's a very small effect, but it can actually have a profound effect on allowing charged particles, particles that have this sort of static electricity on them, to actually remain suspended a lot longer in the air than what would normally be the case if they were neutral or particles that didn't have any charge at all.

23:14 - Paul Alexander, oldest iron lung survivor, dies aged 78

Paul Alexander, oldest iron lung survivor, dies aged 78

A polio survivor, who lived inside an iron lung for most of his life, has died at the age of 78.

Paul Richard Alexander was born on the 30th of January 1946 in Dallas, Texas. He was a bright and able student, but succumbed to a widespread outbreak of polio, which was common, even in first world countries, until the 1953 rollout of a highly-effective vaccine. But that was too late for many, including Paul, who were either killed or left with serious disabilities after contracting it.

Polio is a particularly cruel disease because it mostly affects children under five years old. That said, it is possible to contract it later in life and America’s longest-serving president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was diagnosed with it at the age of 39.

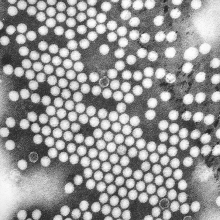

For the majority, the infection is largely asymptomatic, with few or no symptoms. But in about 1% of cases, the virus, which infects only humans and spreads through the air, faeces and in contaminated water, attacks the central nervous system, targeting the motor neurones that control our muscles. It robs them of their nerve supply and leaving victims with weakness and paralysis.

In the summer of 1952, Paul Alexander - who was just six-years-old - began to suffer from pounding headaches, lethargy and a stiff neck. His symptoms worsened and suspicions grew that he had contracted polio. Indeed, many of the public amenities in Texas - such as bars, cinemas and churches - had been closed in order to curb the spread of the virus. Nevertheless, cases continued to grow unabated.

When it was confirmed that Paul had polio, he was taken to Parkland Hospital in Texas. He was so ill that nobody expected him to live, and almost died before it was spotted that he wasn’t breathing. Paul underwent a life-saving tracheotomy so he could be ventilated, and when he awoke he found he was paralysed from the neck down and encased in a metal cylinder called an iron lung, with just his head poking out at the top. He would spend the vast majority of the rest of his life inside the medical contraption.

But how exactly did the iron lung keep him alive for so long? The polio infection effectively destroyed the nerve supply to the muscles that moved Paul’s chest and diaphragm, so he couldn’t breathe for himself. The iron lung rhythmically pulled air in and out from the box he was laying in. This periodically dropped the pressure inside to below atmospheric pressure, so the higher air pressure in the surroundings pushed air into Paul's chest, inflating his lungs.

Paul, however, did not let his illness - or his iron lung - define him. Following an eighteen month stint in hospital, he was allowed to return home. His parents rented a generator and a truck for his iron lung and, with the help of his therapist, he began to practise breathing techniques that would allow him to leave the iron lung for short periods of time.

He was one of the first homeschooled children in Texas and, on graduation from high school, Paul attended Southern Methodist University. In 1984, he gained a law degree from the University of Texas in Austin. He was admitted to the bar two years later, and practiced as a lawyer for a number of years, managing to leave his iron lung and attend court in his wheelchair for a few hours at a time.

In later life, Paul would continue to attempt new challenges - including writing a memoir which took him years to compose using a plastic stick to type on a keyboard and dictating to a friend. He also joined the social media site TikTok in the months before his death, and was recognised by Guinness World Records as the person who lived the longest in an iron lung. Paul’s brother, Philip Alexander, told the BBC how he would be remembered:

Health practitioners have made huge strides in tackling polio in recent years. Since 1988, wild poliovirus cases have decreased by more than 99%, thanks largely to a hugely successful vaccination campaign. Of the 3 strains of wild poliovirus (type 1, type 2 and type 3), wild poliovirus type 2 was eradicated in 1999 and wild poliovirus type 3 was eradicated in 2020. As of 2022, endemic wild poliovirus type 1 remained in just Pakistan and Afghanistan.

28:09 - Why are radiators double sided?

Why are radiators double sided?

Thanks to Dr John Bissell for the answer!

Comments

Add a comment